Earlier this year, a new visitor paid the East Bay a visit. Having flown north from Pinnacles National Park, condor #943, a young male, was spotted soaring over Brushy Peak on June 9, 2022.

This bird was the second California condor known to occur in the Mount Diablo area in more than 100 years.

The condor soared north to Fremont Peak, through the Santa Cruz mountains, and into Henry W. Coe State Park, where he spent the night. The next day he flew east of Lake Del Valle and over Brushy Peak.

By that evening he had returned to Pinnacles National Park. It’s estimated that it took condor #943 a mere three and a half hours to make the journey back from Brushy Peak.

The Pinnacles condor team was able to track his movement with GPS transmitters, which were partially funded through a small grant from Save Mount Diablo through our Dr. Mary Bowerman Science and Research program.

Save Mount Diablo has also just given the team a second grant so that they can track more young condors as they wander.

The Life of Condor #943

California condor #943. Photo by Joseph Belli

After hatching in captivity in 2018, condor #943 was released two years later at Pinnacles National Park.

He drew the attention of the Pinnacles condor team last year, when he was observed with an aluminum can stuck to his bill in Big Sur. It was dislodged in an avian clinic, where he was found to have a high lead level in his system.

After being treated at the Oakland Zoo, he was re-released successfully at Pinnacles.

Now condor #943 appears to do be doing well; his journey is one of the furthest north that has been observed in recent history.

Threats to the Condor Population

Condors in captivity. Photo by USFWS Pacific Southwest Region / CC BY

Although the California condor population is steadily increasing, it still largely relies on captive breeding for survival. According to the Pinnacles condor team, more condors were found dead in the wild than had hatched outside of captivity.

One of the most significant threats to the recovery of the California condor is poisoning from lead bullets. Lead poisoning happens when condors ingest carcasses with lead bullets that were left by hunters.

Unlike other bullets, lead bullets shatter inside the animal, making it easy for a condor to eat fragments of the bullet.

This problem is probably why condor #943 was found with a high lead level last year. Without treatment, this currently healthy condor would have likely perished because of lead poisoning.

Closeup of a California condor. Nathan Rupert / CC BY-NC-ND

Fortunately, in 2019 the use of lead ammunition was outlawed in California. Although condors are still dying from lead poisoning, hopefully the use of lead bullets will decrease with time and further awareness of their harm towards condors.

Another leading cause of death for condors is microtrash. Microtrash can kill condors before they even leave the nest.

Adult condors will often bring their offspring small bone chips to eat along with meat. It’s easy for the adults to mistake small pieces of trash for bone, and if the chick eats enough trash, they die.

Car collisions and electrocution from power lines are also common causes of death for condors.

According to the National Park Service, electrocution was an incredibly common cause of death until biologists created a power pole aversion training program.

Now young condors have a fake power pole in their enclosures that gives them a light shock if they land on it, quickly teaching them a life-saving lesson.

Why Wildlife Corridors Are Essential for Condor Recovery

California condors soar over the Diablo Range. Photo by Sean Burke

The Diablo Range, one of California’s least protected mountain ranges, is playing a critical role in the return of this iconic species. One of the goals of our work is to maintain habitat connectivity within the Diablo Range.

California condors can fly up to 200 miles in a day, the entire length of the Diablo Range—they require large expanses of undeveloped open space to thrive. With a wingspan that can stretch up to 10 feet, this magnificent bird can travel far and wide, if it has a good habitat.

From the Brink of Extinction

California condors are social creatures. Photo by Ken Clifton / CC BY-NC

In the 1980s, California condors were nearly extinct. Because of habitat destruction, lead poisoning, and poaching (including egg collecting), their population was down to 22 individuals. Though they’re still critically endangered, there are now hundreds living in the wild, and they’re expanding their range.

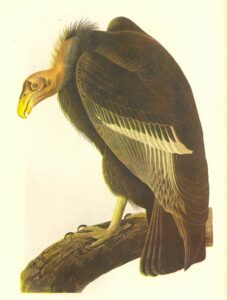

California condor in 1840. By John James Audubon

Last year, a condor flew to the Diablo region for the first time in over a century. That condor had flown further north than any condor since the recovery programs began in the 1990s.

“For years Save Mount Diablo has been saying that as the California condor population grew that they would end up at the peaks and cliffs around Mount Diablo. The Diablo Range is a mountain lion, golden eagle, California condor wildlife corridor freeway—they all follow major undeveloped open space corridors, and that’s exactly what the Diablo Range is,” says Seth Adams, Save Mount Diablo’s Land Conservation Director.

Condor #943’s appearance is a promising sign for the continued recovery of this species. We hope to see more and more frequent sightings as the population grows.

California condors are social creatures—in the 1800s, they could be seen in flocks of 20 or more throughout California.

Perhaps in the future, large flocks of condors will again be a possibility.