As part of our 50th anniversary celebration, we’ve been working with UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library to create a series of oral histories of the empowering individuals who helped create Save Mount Diablo. You can view the whole list and an overview of the project here.

John Kiefer has been one of Save Mount Diablo’s supporters since the beginning. While helping to fund our work, he has witnessed the numerous organizational changes we’ve undergone and been an instrumental force in bringing people together to support the protection of Mount Diablo.

Early Life and Journey through South America

The Menlo Park train station in 1918

John Kiefer spent his childhood in Menlo Park when it was very different from today. In the 1930s and 1940s, Menlo Park was a rural area, “being in—truly in—the country, I was literally surrounded by nothing but open space.”

Now, of course, Menlo Park is a part of Silicon Valley, a global center for innovative technology.

Menlo Park Civic Center in 1965

After attending at college Santa Clara University, John traveled south for months, a transformative experience that would strongly influence his worldview for the rest of his life.

“I had a yearning to travel, and so I had gone to school with a few good friends from Central and South America, and I said, ‘Well, that’s the place for me,’ . . . and being of the earth, I wasn’t interested in museums in the big cities. I spent my time in the country, in the interior, in the jungles, traveling by whatever means, but generally heading south.”

He later went to work as a systems applications specialist for Pacific Bell.

“When I went to work, there were no computers. We had pre-computer machines, and then the computer came, and that required programmers, and so that’s how that evolved. So I spent 30 years with them.”

Moving to the East Bay and Connecting with Mount Diablo

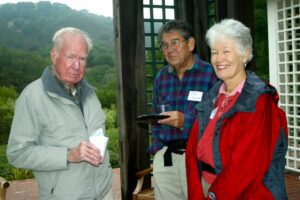

John Kiefer, Scott Hein, and Seth Adams in 2004. Photo by Liede-Marie Haitsma

After living in Los Angeles for a few years, John moved to Lafayette and remains a resident of the city to this day. “It was a one-street town, and it still is.” He quickly grew to love the local parks and open spaces and was outdoors constantly.

“On one side we have marvelous open space, a preserve called Briones [Regional Park]. It has lots of trails, and begs you to come and connect with nature in that environment.

“On the opposite side of my house, looking east rather than west, is this wonderful . . . mountain called the devil’s mountain, Mount Diablo. . . . I was very quickly attracted to experience this marvelous place.”

Mount Diablo holds a special place in John’s heart; its extraordinary topography and ecosystems left him in awe. “There’s something about a mountain. It’s not difficult when you’re on Mount Diablo to pick up a piece of material—call it a stone, if you will—and realize that that is material that was under the ocean.”

Mount Diablo and the Briones Valley. Photo by Stephen Joseph

Spending time on Mount Diablo was a way for him to bond with his family and connect with his own spirituality.

“I started hiking myself with my children, who were then six, eight, and 10. And pretty soon I was leading hikes. . . . For me, to be on the mountain is to connect with the natural world. And in my philosophy and spirituality, the natural world is simply an infinite number of diverse faces of the spirit, so the spirit is there.”

Over the years, John witnessed how Lafayette and the rest of the Bay Area developed. More and more houses flowed into the once undeveloped valleys and up onto some of the ridges.

Fortunately, Lafayette worked to protect many of the ridges surrounding the city; these ridges would continue to remind John of the wonders of the Diablo foothills every day.

“You look around, and you’ll see homes on the top of ridges that you wish weren’t there. That’s not the case in Lafayette. So when you get on top of a hill, you’re looking out and you’re seeing vegetation with an occasional roofline. So yeah, it continues to be a wonderful place.”

His love of the mountain and the hills would draw him to Save Mount Diablo early in the organization’s history.

Art Bonwell, John Kiefer, and Allison Hill in 2004. Photo by Liede-Marie Haitsma

Building Lafayette’s Trails

John’s love of nature drew him to work outdoors, helping to plan and build Lafayette’s widely used trail system. Initially he worked on the parks, trails, and recreation commission for several years, collaborating with residents to plan publicly accessible trails.

Photo by David Ogden

But he would eventually shift focus to the hands-on building and maintenance of the trails.

“I was drawn to work in the field. . . . I was responsible for the design and coordination of the construction of four of those trails, so—three of which are feeder trails, and one is a loop trail. Of the seven city trails, two of them are loop trails that don’t connect to a regional trail, but just provide access to nature for that particular area. And one of the trails that I constructed now carries my name, the John Kiefer Trail.”

Thanks to John’s hard work over the years, Lafayette has miles of trails that connect the city with the Diablo region’s wider trail system.

Involvement with Save Mount Diablo

Hikers at Save Mount Diablo’s Mangini Ranch Educational Preserve. Photo by Al Johnson

“It would be difficult to spend any significant amount of time on the mountain without running across somebody that was connected to the organization Save Mount Diablo,” John says.

“I want to participate in protecting the mountain from development. . . . the natural way that has evolved and has worked extremely effectively over 50 years to protect the gift of the mountain and its environs is Save Mount Diablo.” He started donating to our land stewardship work and has made significant contributions over the years.

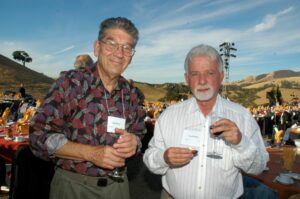

John Kiefer can often be found reaching out to donors or hosting gatherings that bring lovers of Mount Diablo together. He helped start our tradition of hosting community breakfasts, an important part of our outreach work.

“I’ve been active in supporting that. And with my particular focus on connection, I got them to be involved in morning breakfasts, which, from my perspective, simply serves to provide a social setting for people with a shared vision that can come together and physically touch each other, have a cup of coffee, and spend a little time together. So that’s been a very successful outreach on the part of Save Mount Diablo.”

John Kiefer and Vince D’ Alo at Moonlight on the Mountain in 2009. Photo by David Ogden

He’s introduced many people to our work through his love of Mount Diablo and land conservation. “It simply comes up in conversation, because this is a part of who I am and what I do, and the people that I associate with understand who I am.”

Over the years, he saw how Save Mount Diablo changed with the times, as Ron Brown and then Ted Clement led the organization into the future. John predicts that Save Mount Diablo’s work will continue to be needed in the future, perhaps even more so than now.

“I’m confident that it will continue to grow as needed, as our world continues to change. . . . the need continues, and it will be met by the next generation, such as, well, my children, but more importantly, my grandchildren, that hopefully . . . will continue the conservation effort.”

To read more about John’s life and work, view his full oral history.

To learn more about our 50th anniversary oral history project, read our Voices of Save Mount Diablo blog post.

Top photo by Jessamyn Photography