By Floyd McCluhan

Over the course of 16 months and several near-death experiences, what was once thought of as impossible became a reality.

On November 12, 1958, Warren Harding and his partners were standing on top of El Capitan, becoming the first ever to climb the 2,900-foot rock face.

In the process, they pounded 675 pitons and 125 bolts into the granite face in their siege-style climb. Throughout these 16 months, the crew would leave fixed ropes on the wall face, allowing them to go up and down the wall repeatedly.

Two years later, Royal Robbins took on Harding’s route. But Robbins advocated against siege tactics, prioritizing leaving as little as possible on the route.

He championed a clean-climbing ethic, prioritizing using equipment that is not destructive to a mountain’s (or rock’s) environment.

Robbins and his crew repeated Harding’s route in a single push, and in the following year, Robbins and his partners, Chuck Pratt and Tom Frost, established a new route on El Capitan, the Salathé Wall.

This is a climb that is now known as Robbins’ masterpiece, as it embodied his conservation style of climbing; throughout the entire nine-and-a-half-day climb, the crew only left behind 13 bolts.

Harding’s and Robbins’s ascents—though both impressive in their own right—set up a dichotomy for the climbing world: to climb using any means necessary, as in Harding’s style, or to climb as a conservationist, as in Robbins’s style.

Because Robbins showed the world that it was possible to climb major routes in a clean style, that has become the best practice for climbing.

More than 50 years have passed since both of the men’s impressive ascents, and the climbing community still embraces Robbin’s Leave-No-Trace style of climbing.

Now, modern gadgets like spring-loaded camming devices make this style of climbing easier and safer. However, as the growth and popularity of climbing has taken off in recent years, sometimes the clean-climbing ethics Robbins standardized get left behind.

In 2021, a climber marred an ancient petroglyph site in the Moab desert by bolting a route through it. It was such a notable event that it traveled well beyond climbing audiences, and it was reported in many news outlets.

The incident sparked many much-needed conversations about climbing on indigenous land, climbing alongside culturally sacred artifacts, and the continued need to climb with minimal impact.

This article highlights better ways to climb as a conservationist, a principle that modern climbing was founded on. Here are five ways you can climb as a better conservationist.

1. Find the Best Trails

Staying on the granite slabs, walking to Cathedral Peak. Photo by Floyd McCluhan.

Popular climbing destinations such as Yosemite National Park have designated climbers’ trails marked by signs for popular routes and rock formations. Most places, however, are not going to be as well marked.

Likely, climbers are going to be the only ones hiking up to these cliffs and formations, and in the process of going up to these formations, “social trails” are created. Social trails are paths not installed by managers that are usually created by trampling.

Social trails should be kept to a minimum; the more paths that are created going to the same rock formation, the more destruction that will occur. Forging new paths destroys habitat and vegetation and can sometimes spread exotic, invasive plants.

Do your best to find out and follow the designated climbing trail if there is one. One tip is to try searching for a GPX file (especially for long approaches, such as a route at Snake Dike). At the area, take some time to scout out the most promising path.

If you end up going on a trail that leads to a dead end, you can help prevent other people from making the same mistake by stacking some sticks in the entrance on your way out. For paths that you know lead to the climb, you can add cairns.

If all else fails, do your best to leave the most minimal impact possible. Try staying on durable surfaces such as rocks or drainages rather than trampling foliage. With that said, most alpine routes require cross-country travel. Refer to Leave No Trace’s guidance on off-trail travel and use your best judgment.

In this post, you can see the ecological destruction that occurs without any primary paths.

It’s always important to stay on the path, even in desert areas like Zion and Moab where it looks like it’s fine to walk anywhere. There’s a popular phrase, “Don’t Bust the Crust.” As the web page for Zion National Park warns:

“Biological soil crusts contain a complex community of micro-organisms that help to keep the sand in place and provide nutrients and moisture so plants can grow. Thick crusts can be seen as lumpy black areas, much like fungus. When you walk on these living soils, the micro-organisms die. So please don’t “bust the crust” by creating another social trail—even if it is the shortest distance to your climb.”

2. Climb Like a Local

With different crags come different ethics, rules, and rocks. You should know about all three of these things. The Access Fund has a great phrase—and series—called Climb Like a Local that represents this idea, as well as other great climbing advice.

All climbers should be familiar with what the rules are for different rock types. Though rocks like granite are super strong, and generally climbable most of the time, some rocks like sandstone require much more precaution.

Strong sandstone needs at least three days to dry until you can climb on it, and more porous sandstone can require a week. A good way to test to see if the rock is climbable is to scrape away the top layer of dirt. If the top one to two inches of soil are dry, that’s a strong indication that the area has dried out.

Climbers should be familiar with the rules of the area in which they are climbing. If they are climbing at a state park, for example, the park will likely only be open from dawn to dusk.

Many climbs are located on private property that the owner allows to be climbed. In these instances, it is especially important that you make sure you are not overstepping any boundaries. And keep your disturbance level to a minimum (for example, don’t play loud music). Otherwise, you could risk getting the climbing routes shut down for everyone.

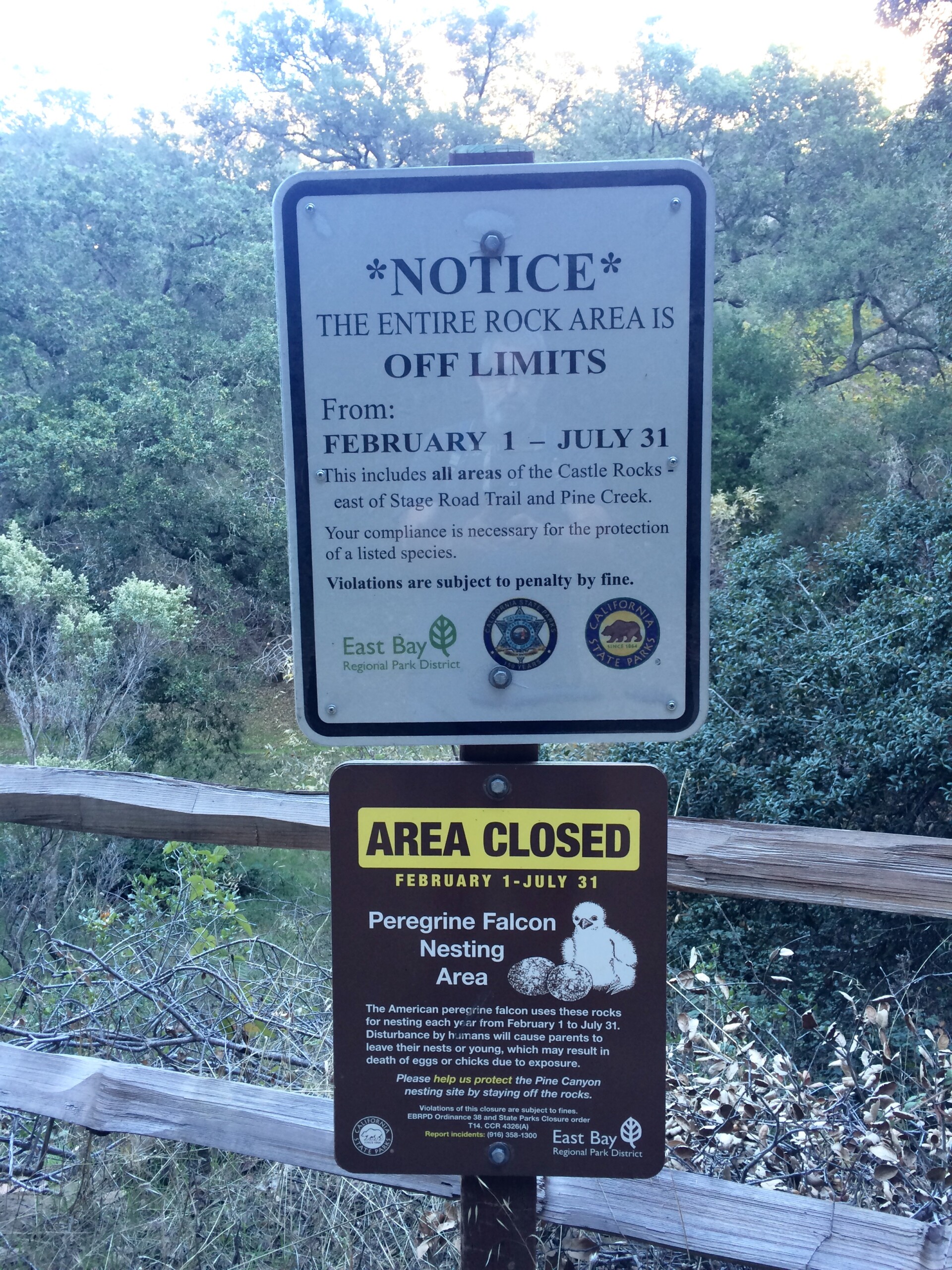

Quite often, many crags and routes are closed for certain portions of the year because of raptor nesting. Please do not threaten these endangered birds to climb a route.

Peregrine falcon closure at Pine Canyon in Mount Diablo. Photo by Seth Adams.

Climbing like a local is a great mindset to have. You wouldn’t want to do anything to jeopardize your home crag, just as you shouldn’t any other. You should climb like a local and a conservationist. If you’re doing both of these things, congratulations, you’re also climbing as a role model.

3. Remember That Rocks Aren’t Just for Climbers

The most famous rock in the world, El Capitan. Photo by Floyd McCluhan.

Gazing up at the monolithic granite formations in Yosemite, or the sublime sandstone cliffs of Zion, you can see that it’s no wonder climbers travel from all over the world to climb there. No matter how crowded the routes may feel that day, climbers will be the minority of visitors. It’s important to keep rocks as pristine as possible for everyone.

Here’s an imaginary scenario. You’re in a national park and just parked at a popular trailhead. There’s a gorgeous steep granite slab right off the side of the trail, maybe only a minute walk away. Even from the parking lot, you can see there’s a tightly spaced bolt line leading to the top. What would you think? It could be easy to get stoked; it’s a safe bolted line that requires essentially no approach.

For other groups, however, it’s an eyesore. How does a bolt help a hiker? Note what the US Department of the Interior has to say about this scenario:

“The establishment of bolt intensive face climbs is considered incompatible with wilderness preservation and management due to the concentration of human activity which they support and the types and levels of impacts associated with such routes.” —NPS Director’s Order 41

Here’s a real account of a similar scenario. In 1970, the Italian climber Cesare Maestri lugged up a 300+ pound gas-powered compressor to the base of Cerro Torre in Patagonia to drill over 400 bolts to the top of the mountain.

Like Harding’s ascent of El Capitan, it was a siege-style climb, but much more intrusive and with bigger impacts. Maestri heard criticism from across the world; the climb was largely considered a desecration of a beautiful mountain.

Of course, bolting has its place in modern climbing, and the question of “to bolt or not to bolt” is one that will be argued to death, and far exceeds the scope of this article. The main point here is to remember that all rocks weren’t originally created to be climbed.

Even the legendary climber Dean Potter was quick to get harsh feedback from his closest friends when he unwarrantedly climbed the Delicate Arch in Utah in 2006. The North Face’s slogan, “Walls are meant for climbing” may have good intentions, but it might not be the most appropriate message.

The US Department of the Interior states, “Climbing practices with the least negative impact on wilderness resources and character will always be the preferred choice . . . Climbers are encouraged to adopt Leave No Trace principles and practices for all climbing activities, including packing out all trash and human waste.”

Although the average climber isn’t bolting routes, many climbers still leave impacts when climbing outside. Boulders often forget to brush off chalk and tick marks when climbing. Season climbers are especially stingy when seeing tick marks, as they give unsolicited beta to people who want to figure out the boulder problem for themselves.

In general, chalking rocks degrades their natural aesthetic qualities, and with darker colored rocks like basalt, this effect is exacerbated. Excessive chalking of routes is just graffiti to the majority of people who don’t climb.

4. Leave No Trace

Using specialized equipment to clean graffiti off rocks. Photo by Sean Burke.

Anyone who is recreating outdoors regularly should be familiar with Leave No Trace’s Seven Principles. In many ways, climbing is a double-edged sword. It allows people to reach incredible heights and remote locations, but it also expands humankind’s impacts.

Even on classic multi-pitch routes, look long enough and you’ll find trash somewhere. In the annual Yosemite Facelift, there’s always an absurd amount of trash to be collected.

One notorious piece of climber litter you’ll find just about anywhere are rope tips. You know the tiny plastic tips that are at the end of the rope when you first buy them? Frequently, climbers don’t remove them, and they’ll naturally fall off with use. If your rope tips are removable, it’s a good idea to take them off before you take your rope outside.

Other litter commonly found at the base of routes includes tape and food wrappers. If you spend enough time cleaning up litter, you’ll likely be rewarded with a free piece of gear like a forgotten carabiner―it seems karma loves climbers.

5. Support Conservation and Climbing Groups

Save Mount Diablo, Bay Area Climbing Coalition, and others teaming up to clean graffiti from a popular climbing crag. Photo by Roxana Lucero.

Since the era of the Stonemasters, climbing nonprofits have been created that work on conservation (as well as other things). The most popular are The Access Fund and The American Alpine Club.

An easy way to support these groups is by donation, but there are also volunteer events happening across the country that focus on restoration, facelifts, retro-bolting, gym-to-crag education, and so forth.

For example, Save Mount Diablo recently organized a cleanup of micro-trash and graffiti at Mount Diablo’s Pine Canyon, and many climbers attended, putting climbing like a conservationist directly into practice.

Different climbing coalitions also exist for different regions (for example, there’s the Bay Area Climbing Coalition for the San Francisco Bay Area region). You can see if there’s a coalition near you. If not, there’s likely a climbing Facebook group near you.

What Can We Do to Leave a Smaller Impact?

Climbing gyms are continuing to pop up across the world, climbing is in the Olympics, and a climbing documentary won an Oscar; climbing is reaching new heights in unexpected ways, and there is no denying that it will continue to grow in popularity.

Legendary climber Peter Croft says that “We need to say goodbye to a past where we could do whatever we wanted, wherever we wanted . . . Even with the best of intentions, we are making a bigger impact than ever before.”

Even in the 1960s, when climbing was scarcely talked about (much less done), Royal Robbins understood the importance of leaving minimal impact while questing up rocks. It’s a philosophy that has continued to this day, and one that should continue to be practiced.

One trait of great climbers is that they are always thinking of ways they can improve their climbing. They’ll ask themselves questions like, “How could I have saved time? How could I have been safer? What did I do well? What did I bring that was unnecessary? What should I have brought?” And so forth.

Within that mix of questions, it would be beneficial to throw in: What could I have done to leave a smaller impact? If we all think about this one question, we’ll all climb as better conservationists.

We are reaching out to various outdoor user groups (for example, through our expanded Discover Diablo program, which this year includes rock-climbing, mountain-biking, and trail-running events) to invite them into our conservation team. Building more connections with these communities helps protect the natural areas we all recreate in.

Top photo: Matthes Crest. Photo by Floyd McCluhan