Our Mary Bowerman Science and Research colloquium earlier this month showcased the latest ecological research on and around Mount Diablo and in the Diablo Range.

It featured research on the California condor, the critically endangered Mount Diablo buckwheat, and the major dieback that is currently occurring near Mount Diablo’s Knobcone Point.

California Condor Research at Pinnacles

California condor. Photo by Jean Beaufort

Erin Lehnert, Condor Program Crew Leader at Pinnacles National Park, and her team have been working with Save Mount Diablo to track the movements of California condors across the Diablo Range.

At the colloquium, Erin spoke about her work with condors and about the importance of the GPS trackers that a grant from Save Mount Diablo helped to fund.

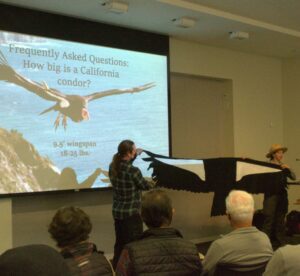

Erin Lehnert and Sean Burke show how big a condor is in real life. Photo by Mary Nagle

She kicked the presentation off with an overview of the condors’ feeding and breeding habits, describing the “condor soap opera” that she witnesses every January and February where mates pair up.

Each condor chick takes months to hatch and a year and a half for each pair to raise.

It’s an intensive process that requires good habitat.

How did California condors nearly go extinct? Besides habitat loss, many factors contributed to their decline.

Settlers used to kill them in huge numbers because they were thought to be a threat to livestock, not realizing that these birds were scavengers.

They perished because of poisoned meat and lead bullets, their population decreasing to just 22 condors in 1982.

Dwarfing birds like the bald eagle with their nearly 10-foot wingspan, condors can fly far in search for food. A single condor can fly nearly the length of the entire Diablo Range in a day—to fully track their movements, long-range GPS trackers are needed.

In 2022, Save Mount Diablo helped to fund nine GPS trackers that were used to track young condors, who are the most likely to wander north. Next year, we’ll be funding more trackers to expand the research on the condors’ range.

California condor #943. Photo by Joseph Belli

These trackers were able to show researchers the paths of condors like #943. Condor #943 is a young male who in 2022 was the second condor known to visit the Mount Diablo region in over 100 years.

As this species continues to recover, who knows how many more condors will visit Mount Diablo in the next few years.

The Conservation Story of the Mount Diablo Buckwheat

Mount Diablo buckwheat. Photo by Scott Hein

Until its rediscovery in 2005, Mount Diablo buckwheat (Eriogonum truncatum) was thought to be extinct. It had last been observed in 1936 by botanist and Save Mount Diablo Co-founder Dr. Mary Bowerman.

After the rediscovery, California State Parks established the Mount Diablo Buckwheat Working Group, which has helped manage the conservation of this species to this day.

Save Mount Diablo Board member Heath Bartosh and Brian Peterson amid a field of rare Mount Diablo buckwheat wildflowers that they found in May 2016. Holly discussed this discovery in her presentation. Photo by Scott Hein

Holly Forbes, Curator at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden, told the story of her role and experience with the rediscovered population and the conservation of the Mount Diablo buckwheat.

Initially after the rediscovery, she helped to install cages to prevent trampling.

She also collected the some of the buckwheat’s microscopic seeds so that they could be grown at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden nursery.

Cultivating the seeds at the UC Botanical Garden was a success.

Starting small, with an 11.8 percent germination rate, the UC Botanical Garden took years to build up their seed supply of this plant.

After nearly two decades of work, they have hundreds of thousands of Mount Diablo buckwheat seeds in storage.

The bulk of the research surrounding this plant is focused on better understanding its ideal habitat and identifying potential reintroduction sites.

Though researchers have found that the buckwheat does well in the nursery, finding a good habitat in the wild is more of a challenge. Since 1936, only three populations have been found growing in the wild. Efforts to plant at new locations have yielded modest results.

Mount Diablo buckwheat growing at the UC Botanical Garden. Photo by Mary Nagle

Interestingly, it was determined that it was most likely abiotic factors, not wildlife that were challenging the reestablishment of this species.

Despite initial concern about trampling, researchers now think the buckwheat requires very specific environmental conditions to thrive.

Holly also informed the audience that this extraordinary plant self-pollinates when pollinators aren’t present.

Today visitors to the UC Botanical Garden can see the Mount Diablo buckwheat in person, growing in an educational display.

As we continue to learn more about this plant, its story teaches us about how a species can be brought back from the edge of extinction.

What Caused the Major Dieback on Knobcone Point?

Dieback on the slopes of Knobcone Point. Photo by Sean Burke

In late 2020, an extraordinary event began to unfold on Mount Diablo’s Knobcone Point. Trees and shrubs have been experiencing dieback.

Although many of them are knobcone pines that have been reaching the end of their normal lifespan, that doesn’t tell the full story of why this has been happening.

After extensive research, researchers were able to determine other factors contributing to this dieback.

Plant pathologist Dr. Tedmund Swiecki and his team took numerous samples of different species from the dieback area to test for different insects, stressors, and diseases.

Most of the samples were taken in areas that bordered roads and trails because they had the largest risk of damage or disease.

When something like this happens, there’s always a risk for a soil-borne Phytophthora disease; it’s a serious issue and can cause irreversible damage to a plant population. (One particular species of Phytophthora is responsible for sudden oak death. Other species cause other diseases.)

To test for Phytophthora, the researchers dug up roots from the plants and used green pears to test for the pathogen. If the pathogen was present, the pear would get infected, and the pathogen would be subsequently isolated. The team tested in 23 different sites.

Dr. Swiecki answers questions after his presentation. Photo by Mary Nagle

At the colloquium, Dr. Swiecki announced to loud applause that there were no soil-borne diseases found!

But if the cause of the dieback doesn’t appear to be soil-borne disease, then what could it be?

The entire area is located on sandstone, with a thin soil layer.

In recent years this area has been particularly affected by drought.

An increasing water deficit has stressed this area and made the plants that grow there vulnerable to heat waves that have been worsening because of climate change.

In the summer of 2020, the area experienced record-breaking heat waves. The high temperatures left the plants with heat scorch: the tops of the plants were essentially burned off.

The heat was a significant stressor for the already water-deprived plants and intensified the first dieback that started in late 2020.

The 2021 heat dome in the Pacific Northwest had similar impacts on stressed forests.

In the years following 2020, Knobcone Point has been continuing to experience increased mortality.

Dr. Swiecki collects samples for his research. Photo by Scott Hein

During the survey, researchers discovered what was prolonging the dieback among the knobcone pines; it was an insect called the California fivespined ips (Ips paraconfusus), a bark beetle that proliferates in stressed areas and fresh slash.

Following the beginning of the dieback, the conditions were perfect for this beetle to breed and thrive before moving to living trees.

It infests and kills affected pines—an infestation caused major tree mortality. Dr. Swiecki determined that the California fivespined ips was the cause of a second dieback in 2022.

Now that we know some of the causes of this dieback, stewards are better able to manage this area and work to prevent similar events from happening in the future.

Other Research

Monarch caterpillar on California milkweed. Photo by Sean Burke

The 2022 Dr. Mary Bowerman Science and Research colloquium gave viewers an inside view into these research projects and more.

There were also presentations on Save Mount Diablo’s work on monarch recovery, and on establishing native plant gardens that include plants important to local tribes in collaboration with them.

And there were presentations on the water quality of Contra Costa County’s creeks, and a major wildlife health assessment performed by the East Bay Regional Park District.

Check out the video of the presentation if you want to learn more about any of these projects!