Story by Joan Hamilton

Hugh Safford is the regional ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region. Years of experience have honed his ability to look at a blackened landscape and predict the future of its plants and animals. In October, he drove into the footprint of the Santa Clara Unit (SCU) Lightning Complex fire to assess the damage.

The fire itself had been impressive. Starting August 18, 2020, the SCU fire burned for 44 days. From the foothills of Mount Diablo in the north to Henry Coe State Park in the south, the flames spread across 625 square miles of the Diablo Range in six California counties. Grazing lands were reduced to ash. Two hundred forty-eight structures were either destroyed or damaged. After the flames died down, the SCU jumped to third on the list of the largest fires in California history.

Even so, Safford describes the SCU fire’s ecological impact in positive terms. “I didn’t see anything that surprised me,” he said after surveying a huge ranch in the heart of the fire footprint. “For the most part, it was like a really big, well-carried out prescribed fire.”

Grasslands will come back quickly after the first rains, he says. Though the moonscape left of the range’s shrub lands (chaparral) might look alarming, Safford says, “it was just your standard chaparral burn—sometimes burning to the ground. But it will come back, either by sprouting or by seed.”

In woodlands, the fire generally stayed low, clearing out small trees and bushes and sparing most of the region’s iconic oaks. “It’s uncommon to have a fire that kills more than 5 to 10 percent of the oaks in a stand,” Safford says.

Where the fire did incinerate oaks, it was often aided by Pinus sabiniana, also known as gray pine. “Where you’ve had pine invasion in oak stands, you can always expect the fire to burn much hotter than elsewhere in the landscape,” Safford says. “The gray pine is really flammable. It produces a lot of resin and litter. When fire gets into it, it burns really hot.”

In a nutshell, the SCU burn footprint is currently a mix of

1) grassland is already re-sprouting

2) severely burned chaparral, which will produce spectacular wildflower shows this spring (and next), before the shrubs make a resounding comeback

3) light to moderate woodland “underburns,” which have cleared out shrubs and small trees that compete with larger trees for water and nutrients

4) and “hot spots,” patches of severe fire that reached up into the canopy, killing pines and some oaks.

“There are little spots out there where land owners probably do need to be concerned,” Safford says, where heavy rains could cause erosion on steep slopes this winter or where buildings and ranching infrastructure such as fences, spring boxes, and culverts were damaged. “But the fire effects themselves are nothing to write home about.”

So this year’s Diablo Range fire was far from apocalyptic. But there’s plenty to learn from the story it has etched upon the landscape. Below, we compare the SCU to other 2020 mega-fires and explain how fires work.

Photography by Bruce and Joan Hamilton, and Cooper Ogden

Are Fires Too Frequent?

Fires that are too frequent can lead to habitat loss. Trees and shrubs, especially those that reproduce from seeds, don’t have time to bounce back, and weedy species invade. That’s one big ecological worry following the LNU fire that lit up Lake, Sonoma, Solano, Napa, and Yolo counties in the fall of 2020, around the same time the SCU fire was burning to the south. Some parts of the LNU, especially near Lake Berryessa, have burned four or five times since 2000.

Ecologist Hugh Safford says that when severe fires occur more than about once every 20 to 30 years, obligate seeding species (such as some ceanothus and manzanita species) may suffer. If fires come more frequently than every 15 years, even species that can re-sprout from their roots (such as bays, oaks, and chamise) can be harmed. Under such conditions, Safford says, “the system often transitions to a shrub-dotted weedy grassland, a condition readily viewable on the lower slopes of many of the southern California mountains.”

Conversely, fires that are too infrequent can lead to choked watersheds with diminished abilities to keep plants reproducing, provide habitat for wildlife, maintain streamflows, and sequester carbon. A lack of fire is a major problem in much of northern California, including the Diablo Range, at least until recently. The culprits? Removal of Native Americans’ cultural burning and suppression of fires. Safford found that large portion of SCU fire footprint hadn’t burned in at least 120 years.

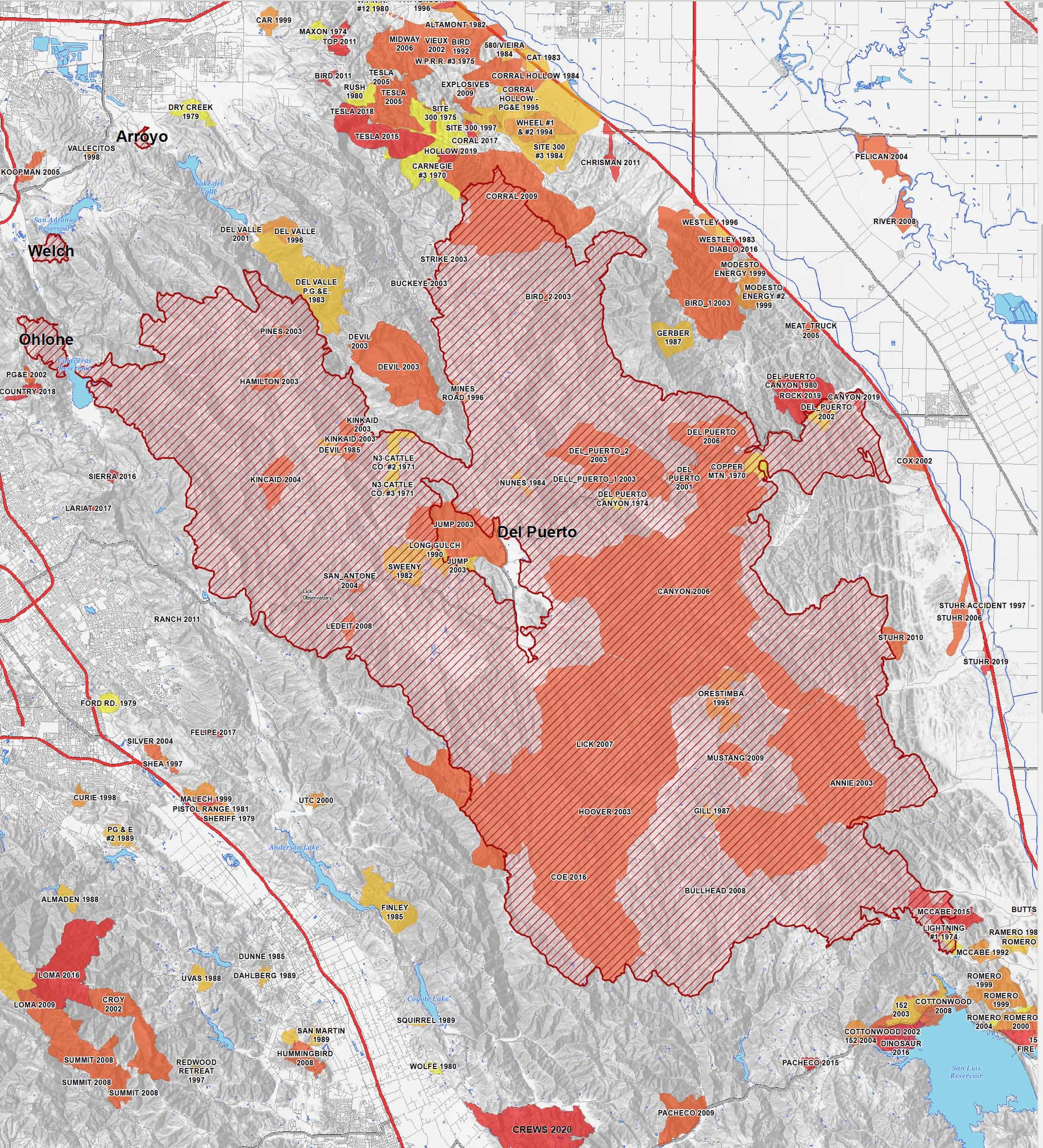

Map courtesy of CAL FIRE

See for yourself on this map of fires in the central part of the Diablo Range since 1970, where infrequent fires have been the rule, up until recently at least.

Coastal Comparisons

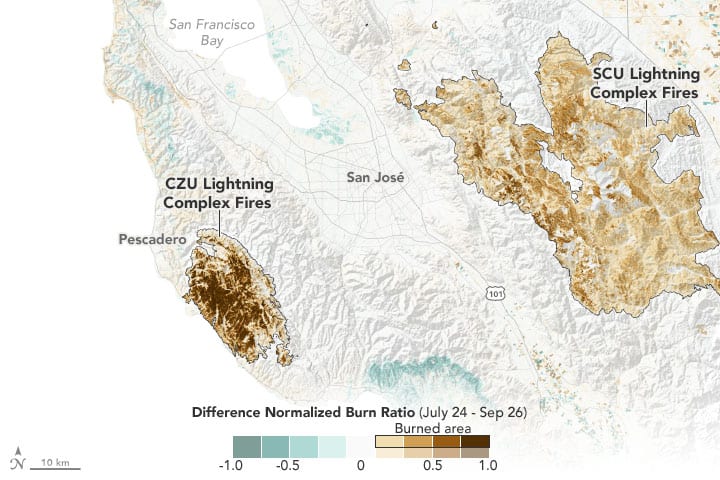

The National Atmospheric and Space Administration collected satellite data on July 24 and September 26 to measure changes in the greenness of the landscape before and after the peak of California’s 2020 fire season. The map shown here compares those changes in the CZU fire (near Santa Cruz) and SCU fire zones. Dark brown areas had little to no vegetation left after the fires last fall. Tan areas were burned, but still had some live vegetation.

Map courtesy of The National Atmospheric and Space Administration

As the map shows, vegetative losses were much greater on the coast than a mere 50 miles to the east in the SCU fire footprint. Botanist and fire expert Heath Bartosh says that the difference is partly explained by “the structure” of the vegetation. The Diablo Range is dry and rocky. It has lots of blue oak woodlands and shrub lands with fuels spaced widely apart. In addition, the SCU’s oak woodlands don’t offer as much “ladder fuel” (layers leading up to a leafy canopy) as do the forests of Douglas fir, tanoak, and redwood farther west.

Moreover, “there’s a lot more fuel in the Santa Cruz Mountains because of the climate and availability of water,” Bartosh says. “And so when they are dry, they burn hotter.”

Polka-Dot Hot Spots

Photo from Bruce and Joan Hamilton

Chaparral fires often leave a ghostly landscape of blackened shrub skeletons. In places where the fire burns hotter, even the skeletons burn up, leaving only the plants’ root crowns or “burls” poking up a few inches. In the SCU fire, however, ecologist Hugh Safford found whole slopes where even the root crowns were incinerated, leaving only holes filled with white ash. Each ashy dot memorialized what Safford calls “a jackpot of fuels,” where a manzanita, ceanothus, chamise, or other shrub had succumbed to the fire.

“I’ve seen that before, but not on this scale, where there were whole hillsides with all the burls burned out,” Safford says. “Probably that’s because there was so much fuel on that site. Those areas hadn’t burned in more than 100 years. Plus, the fire occurred in the hottest part of the summer.”

What’s likely to happen in these hot spots? “I’m sure there’ll be an amazing flower show,” Safford says. “And probably the shrub response will be just a little bit slower because they’ll have to come back through seedling recruitment rather than through re-sprouting.”

The Way Fires Work

Photo from Bruce and Joan Hamilton

Though their depredations may seem random, fires generally follow certain rules. “I can look at a map of fire severity and make a good guess about the vegetation, slope, prevailing winds, and aspect of a place,” says ecologist Hugh Safford. Here are some of the factors that help explain the SCU fire’s hot spots.

WIND—Wind literally fans a fire, so a windward slope (facing prevailing wind) is going to burn hotter than a leeward slope (protected from wind).

SOILS—Habitats underlain with less fertile soils tend to burn less severely than neighboring places. Serpentine soils, for example, are high in heavy metals and low in essential plant nutrients. A haven for native plants adapted to these conditions, they don’t support much biomass overall. “It’s not uncommon for those kinds of sites to come through a fire with very little burning,” Safford says. “This might be one reason that serotinous conifers like knobcone pine and various cypresses are common on serpentine and similar soils. The relative lack of burning gives them time to become adults and generate a seed pool in preparation for the big fire when it comes.”

SLOPE and ASPECT—As anyone who has ever gazed at a candle knows, fire burns upward. That’s why a slope is going to burn hotter than flat ground: the fire preheats the fuels above it as it climbs a hill. And the direction a slope faces, its “aspect,” matters too. South slopes burn hotter than north slopes because they’re usually drier.

VEGETATION—Some chaparral shrubs, such as ceanothus and chamise, have stringy bark that’s easy to burn. Manzanita has smooth bark that isn’t so flammable. Chaparral burns hotter than woodlands, and pines burn hotter than oaks. “But elder oaks can get heart rot,” Safford says. “Crotches in the tree accumulate humus and leaves. Then a spark can burn into the center of the tree and kill it.” The list of plant eccentricities goes on, with many differences that can affect the severity of a burn.

The interplay of all these variables—wind, soils, slope, aspect, and vegetation—lend an interesting patchiness to any fire footprint. Though far from an inferno, the SCU fire swept up into the forest canopy in places, Safford says, creating patches of a few acres where even the largest trees were killed. “I’m not suggesting that’s ecologically bad,” Safford says. “That’s just the way the landscape works.”