The Diablo Range is recovering well from its 2020 mega-fire. But other parts of the state have not been so lucky. Why is the Diablo Range different and how can we keep it that way?

By Bruce and Joan Hamilton

By late December, 2021, a severe burn on the steep slopes of Morgan Territory Regional Preserve was staging a strong comeback from the 2020 SCU fire.

After generous late-fall rains, the Diablo Range is hastening its recovery from the massive 2020 Santa Clara Unit (SCU) Lightning Complex fires. If you head out to the fire footprint, you’ll see oaks pushing out new leaves, black chaparral sticks swamped by new growth, and grasslands so green it’s hard to tell there ever was a fire.

If the rain keeps coming, a spectacular display of wildflowers could emerge this spring.

Wildlife is resurgent in areas hit by the SCU, too.

- A post-fire study on East Bay Regional Park District lands shows higher wildlife diversity and occupancy estimates in burned areas than in unburned areas, particularly for bobcats, gray foxes, and black-tailed deer, not to mention wild boars. Why? Perhaps it’s easier for predators and prey to see each other and move around in the burn, says wildlife ecologist Sue Townsend.

- A park-district study in the Ohlone Wilderness found that most small vertebrate species survived the fire. Total snake and amphibian captures in the area declined post-fire, but total lizard and mammal captures increased—fence lizards and deer mice significantly.

- A U.S. Geological Survey study found that 36 of the 37 golden-eagle pairs known to be nesting within the SCU fire perimeter returned in 2021.

These and other data demonstrate, yet again, that California’s native flora and fauna can bounce back from fire. Looking statewide, however, it’s also becoming evident that there are limits to that resilience.

Two Fires of Similar Size

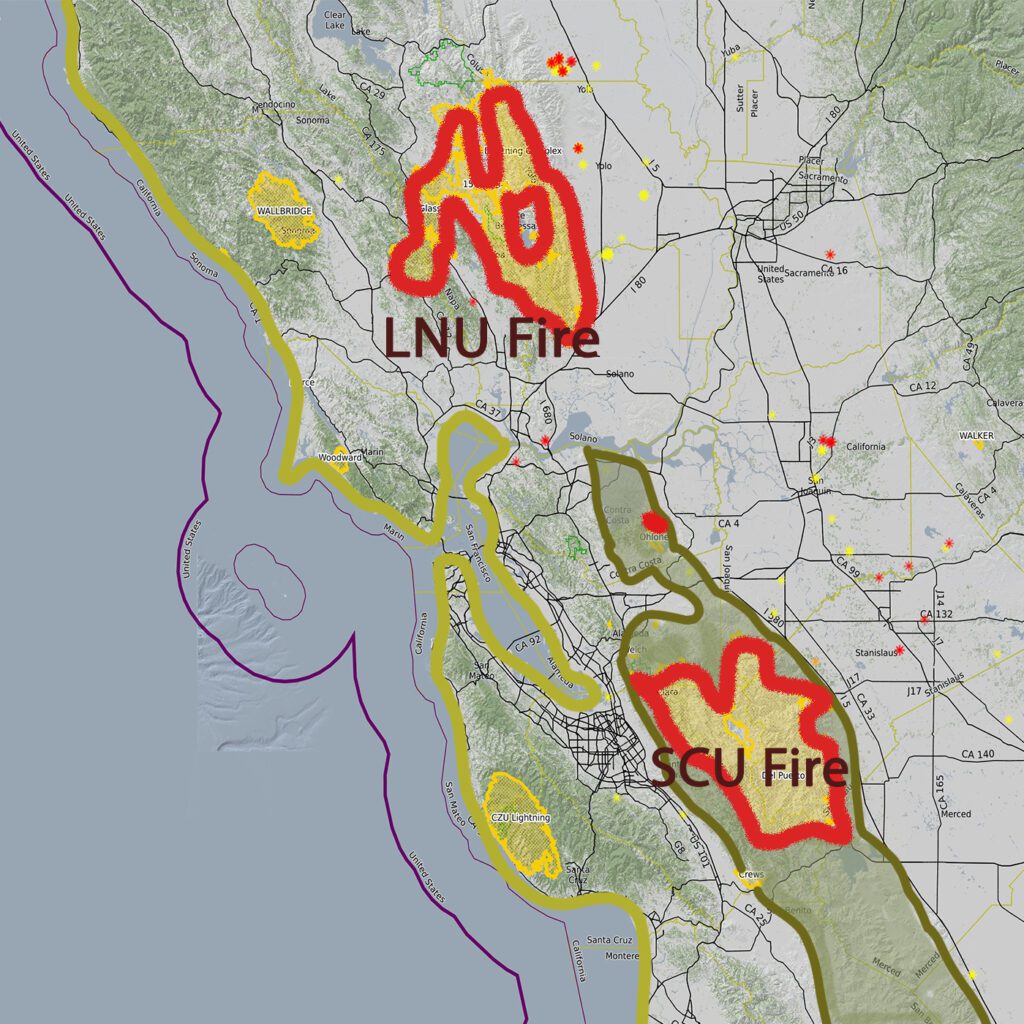

Two 2020 megafires in California’s Inner Coast Ranges were about the same size, but the LNU fire contributed to the degradation of biologically rich shrublands or “chaparral,” while a different history in the footprint of the SCU fire produced different results in the Diablo Range (outlined in dark green).

Around the same time the Diablo Range was burning almost 400,000 acres in the southern part of the Inner Coast Ranges, the LNU Lightning Complex Fire was burning more than 360,000 acres in the northern part of the Inner Coast Ranges in Napa, Sonoma, Yolo, Lake, and Solano counties. Oak woodlands are recovering in both places. But another important plant community, shrubland or “chaparral,” was hard hit in the LNU.

Frequent fires have caused “a wholesale loss of chaparral on a lot of the LNU landscape,” says Hugh Safford, a research ecologist at the University of California at Davis. “It’s been replaced by (non-native) grassland.”

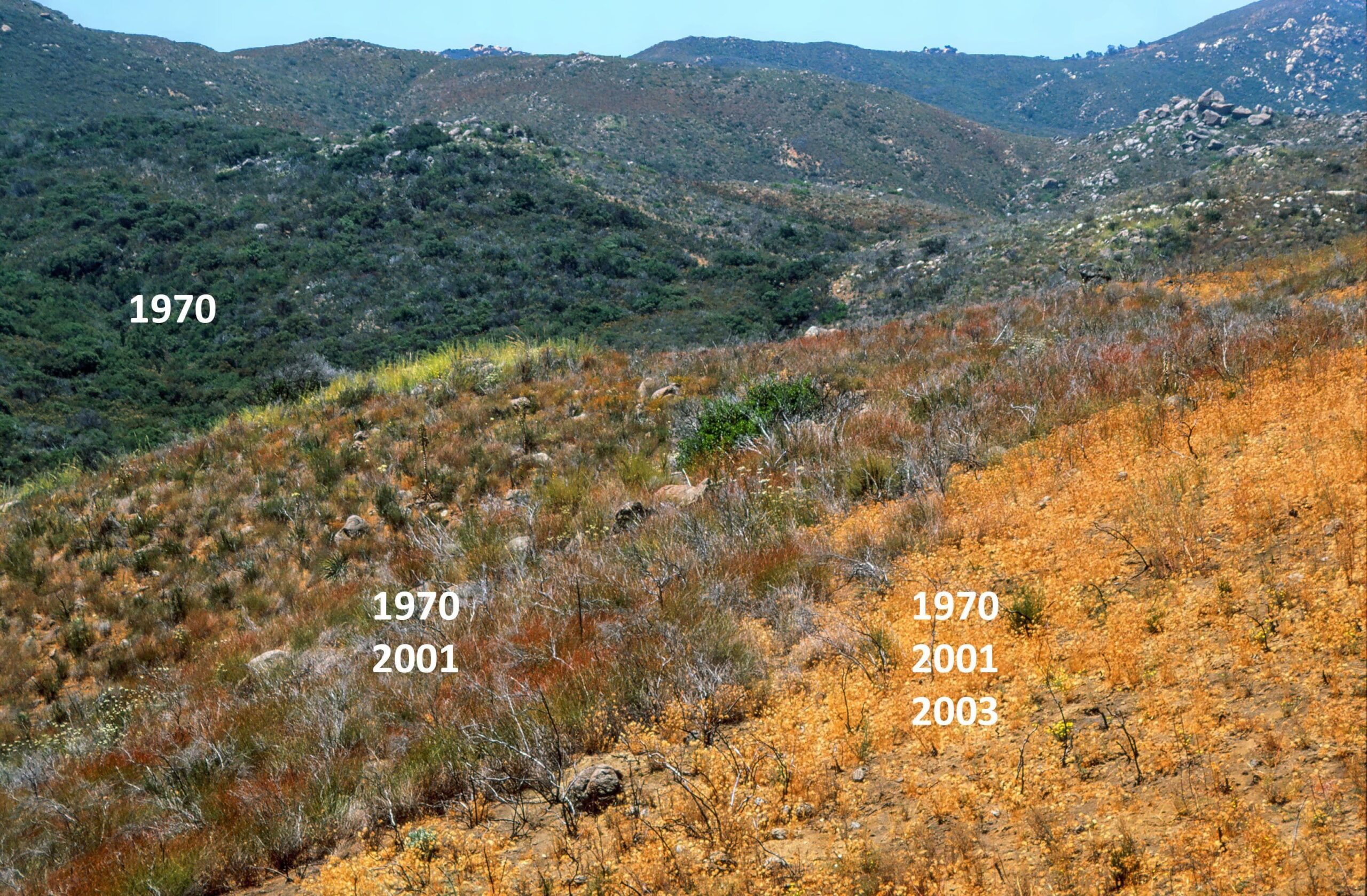

Too many fires in chaparral can transform—and diminish—a landscape. This photo was taken by California Chaparral Institute Director Richard Halsey in San Diego County a year after the 2003 Cedar Fire. The mature chaparral stand on the far left was last burned during the 1970 Laguna Fire. The habitat in the middle, which formed after the 2001 Viejas Fire, retains chamise, sugar bush, deerweed, and other shrubs. The area in the right corner, which re-burned in the Cedar Fire, is filled non-native grasses. Most re-sprouting shrubs have been killed and obligate-seeding species, including some manzanitas, are not present. Ecologist Hugh Safford says that, in general, fire frequencies of less than 15 years kill shrubs and trees that rely on seeds for reproduction. Frequencies of 7 to 10 years or less also kill shrubs that can sprout from their root crowns, causing “type conversion” of chaparral to grassland.

This ecological transformation, called “type conversion,” can lead to even more frequent fires. “We’ve seen conversion going on for decades and decades in southern California,” Safford says. “But it’s now made its way to northern California.”

“Saying that these ecosystems are fire-adapted is sort of misinformation,” Safford says. “Species are adapted to specific fire regimes. You can’t burn a chaparral site more than once every 7 to 10 years or you’re going to turn it into a grassland.” [1]

How the Diablo Range Is Different

Most of the SCU fire footprint experienced fire only one to three times in the past 100 years. In the LNU, though, “There are sites that have burned five or six times in the last 20 years,” Safford says. Some of the difference may have to do with rocky terrain and scant vegetation inside the SCU footprint, but there’s also much less human influence inside the SCU—with fewer roads, encroaching subdivisions, and power lines.

Fewer fires make the Diablo Range a refuge for chaparral, including 20-foot-high manzanitas and thickets of chamise and ceanothus that haven’t burned for a century or more. That’s what California Chaparral Institute Director Richard Halsey calls “old-growth,” a term usually associated with ancient forests.

“Once home to the now-extinct California grizzly bear, old-growth chaparral provides habitat for a wide array of life forms,” Halsey says, “beautiful manzanitas with waist-sized trunks, colorful lichens, and an elfin understory carpeted with a soft layer of fallen leaves and twigs.”

Underground, chaparral shields a seed bank of native-plant embryos waiting (for a fire or other disturbance) to take their turn in the sun. Twenty percent of the state’s native plants species reside in chaparral, though it covers only 9 percent of California’s wild lands.[2]

“Ten years is the minimal amount of time it takes for a burned chaparral stand to mature enough to set enough seed in the soil to create a healthy habitat,” Halsey says. “As fire frequencies increase due to human-caused ignitions, the intervals between fires have been contracting, causing the complete elimination of chaparral in some areas, and serious degradation in others.”

Three Ways to Cope With a Changing Climate

As fire frequencies increase, climate change is decreasing ecosystems’ ability to stage healthy comebacks. In a study of chaparral recovery from a 2015 fire that immediately followed a three-year drought in northern California, Safford and his colleagues found: “Extreme drought and increasing temperatures can decrease the resilience of plant communities to fires.

“Not only may extremely dry conditions during or after fires lead to higher plant mortality and poorer recruitment, but severe pre-fire droughts may reduce the seed production and below ground vigor that are essential to post-fire plant recovery.”

Inside and outside the Diablo Range, conservationists and land managers are considering ways to cope. In forest ecosystems, prescribed (intentionally set) fires are used to reduce fuel loads that could cause a major blaze. The argument is that these forest ecosystems evolved under frequent low-intensity fires and prescribed fires can safely reestablish that pattern.

Halsey warns against using this approach in chaparral, however, because chaparral thrives with infrequent, higher-intensity fires. “It sounds counter-intuitive, but the hotter the fire the better,” he says. In many chaparral species, a high-intensity fire stimulates reproduction, regrowth, or re-sprouting.

A second approach to protecting ecosystems in places where fires are too frequent is the familiar (and historically overused) tool of fire suppression. Once land managers fought as many fires as they could—and their lands suffered from a buildup of fuels. Currently, fire-fighting resources are focused on protecting human life, property, and infrastructure. But they could be harnessed to protect some of the state’s rarest, most important plant communities, too.

“Chaparral communities over 75 years old are top priorities for protection,” Safford and colleagues urge in The Past, Present, and Future of California Chaparral, “not only because of the remarkable biodiversity they support and the ecosystem services they provide, but also because of impending threats from urban development, fragmentation, increased fire frequencies, invasive non-native plants, and warming temperatures.”

In southern California, the Forest Service has already vowed to “to expand fire prevention efforts to retard the loss of native ecosystems like chaparral and coastal sage scrub.”

The third and probably most effective tool for fighting too-frequent fires is land protection. The Diablo Range is a quieter, more isolated place than the fire-plagued lands to the north and south. Its fire regimes are still mostly in balance with the needs of its ecological communities.

It’s still providing a refuge for California plants and animals in a rapidly changing world. If new human incursions—including roads, dams, towns, power lines, OHV playgrounds, and housing developments—can be kept to a minimum, it has a better chance of staying that way.

[1] According to Safford: With less than 15 years between fires, species that depend on seeds to reproduce disappear (including pines and some manzanitas and ceanothuses). Seven- to 10-year intervals eliminate even species that can sprout from their root crowns (including chamise, toyon, oaks, and bay).

[2] Parker, V. T. (2016). Mooney, H.; Zavaleta, E. (eds.). “Chaparral.” Ecosystems of California. Oakland, CA: University of California Press: 479–507.

Photos by Joan Hamilton