By Seth Adams, Land Conservation Director, Save Mount Diablo

It was supposed to be 108 degrees, so we postponed to the following weekend, when it was only 99. Joseph Belli, a conservation biologist and the author of The Diablo Diary, was my companion and guide in exploring the Panoche area, a piece of the San Joaquin Desert in the Diablo Range.

I picked him up east of Hollister near his home in Pacheco Pass. We had five rare and unusual species on our search list. Because some were nocturnal, we’d be exploring all day and late into the night.

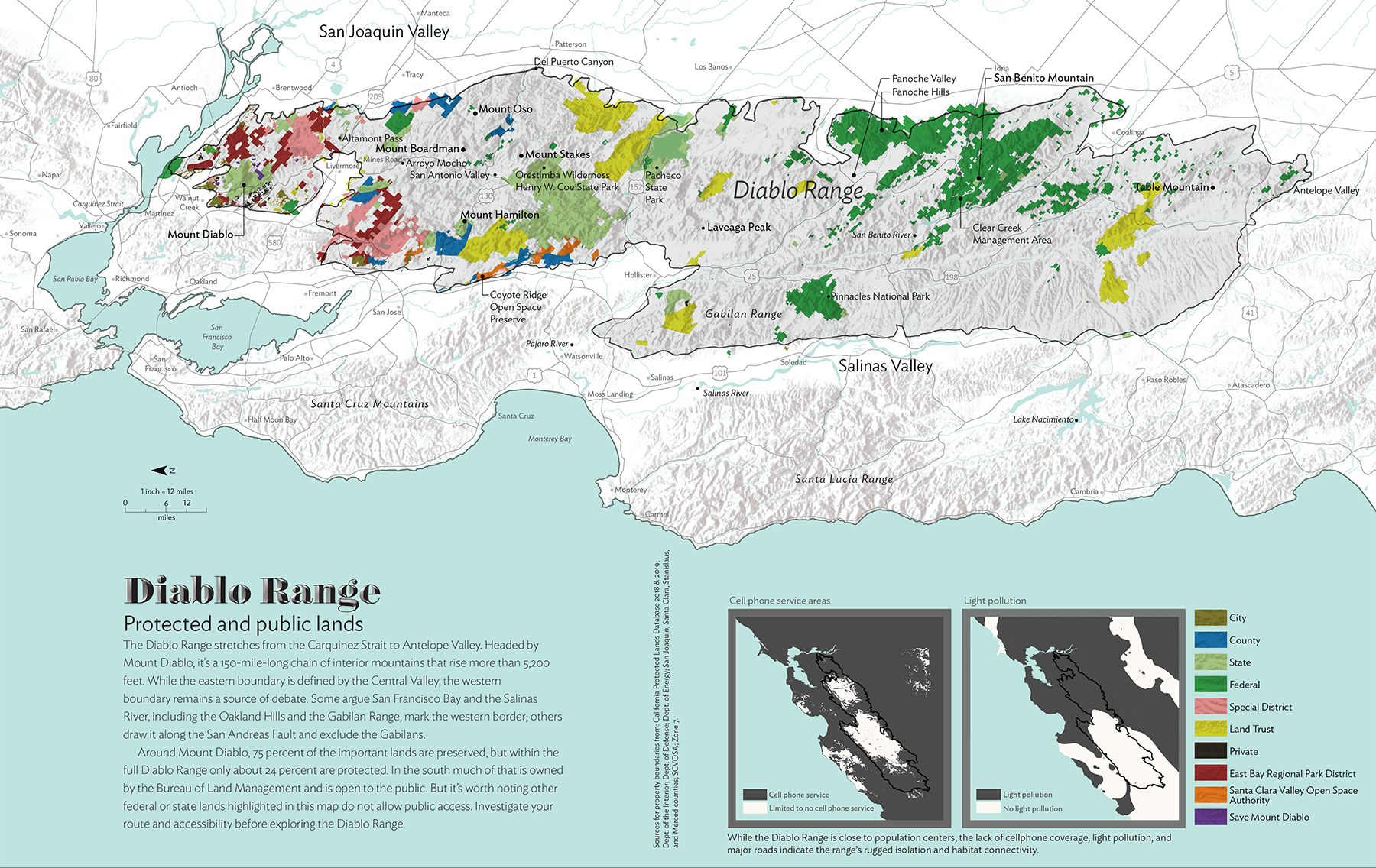

Save Mount Diablo has expanded its geographic focus further south down the 200-mile Diablo Range to the Santa Clara County line. We have also undertaken popularizing the entire 12-county range. We sponsored the first publication about the entire Diablo Range in Bay Nature magazine in spring of 2020, along with the first map of its public lands.

The 2020 SCU fires, 396,000 acres stretching from east of Mount Diablo south to Henry Coe State Park, near Belli’s house, were a ready-made opportunity to educate the public about the northern part of the range. For three years, our Diablo Range Revealed project is describing what we learn about the burn area and its regeneration.

The project will cover a huge area and will help fill in a blank space on the map for the public with roads, wildflowers, creeks, peaks, and place names. However, it’s still localized to the northern part of the Diablo Range. Much of the project is focused on the winter and spring. I needed other ways to explore more of it, especially in the summer and fall.

When we started our work on the Bay Nature magazine article in fall 2019, Bay Nature staff suggested looking for the “John Muir” of the Diablo Range to write about it. There are lots of experts about parts of the range, about Mount Diablo, or Henry Coe, or Pinnacles. Experts about the large BLM holdings further south, or about San Benito Mountain, its highest peak.

But there are no experts about the entire Diablo Range. I told them, “What we need is the William Brewer of the Diablo Range.” Brewer helped lead the California Geological Survey in the 1860s, and his journals were collected as Up and Down California, describing the survey’s exploration of the state.

View of Panoche Valley from San Benito Mountain. Photo by Stephen Joseph.

Eric Simons, an editor at Bay Nature magazine, ended up doing a remarkable job researching and writing the Diablo Range piece, about Save Mount Diablo’s initial explorations.

The “John Muir of the Diablo Range.” Joseph Belli might come closest. Earlier this year, I found his book, The Diablo Diary, which he self-published in 2017. Belli is a character, 59 like I am. He grew up in the Diablo Range, and his father has leased various cattle ranches there.

After a career in the family business, Belli went back to school for a degree in conservation biology and moved to a house on 55 acres in Pacheco Pass that he tongue-in-cheek calls the “Pacheco Pass Wildlife Research Station.”

Belli’s resume includes things like walking a thousand miles in Henry Coe State Park over seven years to survey all the ponds for red-legged frogs and other amphibians. Sampling watersheds for Western pond turtles. Snipping the tails of spiny lizards for DNA sampling. Thousands of hours tracking reintroduced California condors around Pinnacles.

His stories are about chasing tule elk and pronghorn. Experiences with mountain lions. Things like that. A friend admired his writing and suggested he collect his stories and essays, and they became The Diablo Diary. Joseph Belli eats, breathes, and sleeps the Diablo Range and its wildlife.

Seth Adams and Joseph Belli exploring Panoche Valley. Photo by Seth Adams.

I’ve found people like him a number of times in my career—the ones who can take you to the best spots, have the most spectacular photos, have the inside track. For Mount Diablo I might be that person, but not for the entire Diablo Range. There is a kind of no-limits enthusiasm to that brand of passion and obsession.

I did a little online research, found Belli’s contact info, and called him. A few hours on the phone, and then I drove down to meet him in May. Seven hours of conversation.

When I suggested “Show me around. Let’s do a trip a month exploring the range and looking for unusual wildlife”—understanding that we had just met—his answer was something like, “That’s a cool request. Sure, sounds intriguing.” Serendipity. He told me later it was pretty cool to discover someone of the same tribe. The first trip was in June, to Panoche.

When you focus on Central Valley endangered species like San Joaquin kit fox, Panoche-Ciervo keeps getting mentioned. And when you get there, you see that one of its biggest issues the past decade has been a large 1,300–acre solar farm that has impacted a large area of endangered species habitat, but has also helped preserve around 25,000 acres as habitat mitigation.

The solar project had the small ranching community up in arms—those who opposed the project, and those who sold land for it. Belli writes about the controversy in The Diablo Diary.

A handpainted sign protesting the development of solar farms in Panoche Valley. Photo by Al Johnson.

It wasn’t my first time in Panoche. Maybe you’ve driven southeast from Hollister, past the Panoche Inn, one of only two commercial establishments there. Or maybe the other, Mercey Hot Springs, drew you off the beaten path from Highway 5. One time I was trying to get through the New Idria mercury mining ghost town and up the backside of San Benito Mountain.

For the Bay Nature article in December 2019, we did a road trip from Mount Diablo to San Benito Mountain, the Diablo Range’s tallest peak, with stops along the way. I did survey trips beforehand to set it up, including to Panoche.

Panoche, where legendary bandit Joaquin Murrietta supposedly holed up, and was later captured. Pa-Noche, according to the locals, rhymes with “roach.” I braved miles of washboard roads, through Griswold Canyon, and tried to get to New Idria, but the road was blocked.

The first day of the Bay Nature road trip, we’d had a long day already, and we had maybe an hour left before sunset, on our way south to Coalinga for the night. But we had two excellent photographers along and it was magic hour, when the light is low and beautiful, and the shadows lengthen out. Time limits be damned.

Panoche Valley at magic hour. Photo by Stephen Joseph.

We drove east from Highway 5 into Little Panoche Valley, past Mercey Hot Springs and the Panoche Hills BLM unit. Then down into the bigger Panoche Valley to the Panoche Inn, and back out. Just a couple of five-minute stops, but we got spectacular photos.

The next day we saw it again, from the top of San Benito Mountain. The Diablo Range was dark and rugged and complicated. Panoche stretched north, nearly treeless, bathed in sun, arid and big.

Eighteen months and a pandemic later. Five species on our search list. Blunt-nosed leopard lizard. Antelope squirrel. Spiny lizard. Kangaroo rat. And the least likely, often associated with kangaroo rat, federally endangered San Joaquin kit fox.

Panoche is one of three centers of the San Joaquin kit fox’s population. I’ve been searching for kit fox for 35 years without success. Rare and endangered species are, by definition, rare. We would be ecstatic if we found one of the five species.

We found three.

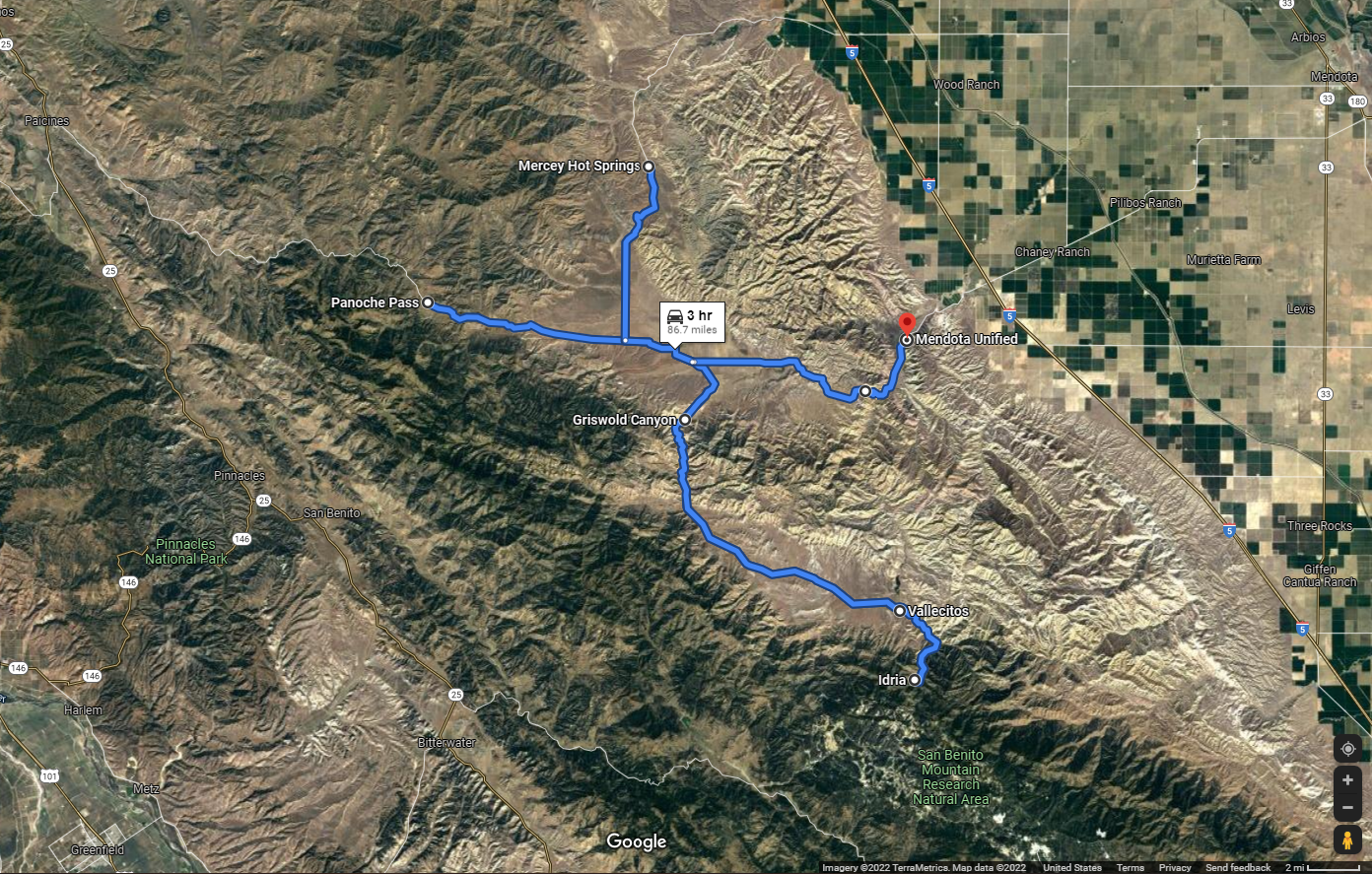

Map of the routes Seth Adams and Joseph Belli explored in Panoche in search of rare and endangered species.

We entered the main valley from the west, from Highway 25 at Paicines, on Panoche Road through Panoche Pass. Another one of those “most beautiful roads in the Diablo Range.” We passed the Panoche Inn, and the Little Panoche Road (up to the solar farm and Mercey Hot Springs; we saved those for later).

The landscape changed from grassland to desert, the road lost its pavement, and our speed dropped to 10 to 12 miles an hour as we scanned for wildlife. The creeks were green threads in desert. We crossed a wet ford of Panoche Creek and up along the edge of huge Silver Creek Ranch, protected as part of the mitigation for the solar farm.

You have to piece together information and maps from many sources to get a better picture of the solar farm habitat impacts and mitigation, but both are significant: the solar farm was downsized in years of legal challenges to 1,300 acres or about two square miles of critical habitat.

Meanwhile around 25,000 acres—almost 40 square miles—has been preserved on the valley floor and in two nearly 11,000-acre ranches, the Valadeao Ranch and the Silver Creek Ranch. They fill in big open-space gaps like puzzle pieces next to BLM’s Panoche Hills unit, and connect Panoche Hills, Tumey Hills, and Griswold Hills.

A no trespassing sign protecting a critical conservation area in Panoche Valley. Photo by Al Johnson.

Panoche Road crosses the northern part of Silver Creek Ranch. We stopped frequently. It was hot but with a breeze. Would the wildlife all be underground in the middling heat? Squirrel!?! Antelope squirrel! One, then another, and eventually more. A “species of special concern,” meaning it could become endangered in the future. Maybe 12 in all. The unpaved road continues over Jackass Pass to Highway 5, but we turned back.

That same hour in the same vicinity, Joseph saw them first: Blunt-nosed leopard lizards. Federally endangered. A more colorful female, a more block-headed male. We hit the jackpot! Fast! From one burrow to another. They spend much of the year underground, so we got lucky. We spent quite awhile watching them. We continued our creeping drive.

A blunt-nosed lizard basks in the sun. Photo by Joseph Belli.

Back in the main valley, we headed toward Griswold Canyon and over to Vallecitos, our second major valley and where Joseph had seen a kit fox some years earlier. That road is more potholes than pavement and leads to New Idria and toward San Benito Mountain, miles further south.

Much of the canyon was in shadow and the spiny lizards were hiding at a location Joseph had previously sampled. Then into sunny Vallecitos. No kit fox. We knew it would be a long shot on any drive, but we still had the night ahead of us.

Wide valley, rugged Diablo slopes, a succession of creeks. This time the road wasn’t blocked. New Idria. We headed up the gorgeous canyon along mercury-laden San Carlos Creek. Joseph’s friend, journalist Kate Woods, had lived in the canyon for years, and he had been there many times. The town site attracts an array of visitors, some sketchy, and we were 30 miles or more off the beaten path.

Back through Vallecitos and into darkness, but the moon rose nearly full. More dirt roads. Looking for nocturnal species like kangaroo rats in our headlights. One species is endangered. Maybe the cat-sized kit fox.

Up Little Panoche Road past the solar farm toward Mercey Hot Springs. In the pass, Joseph had seen swarms of kangaroo rats at one point. We speculated whether the nearly full moon would keep them underground, since their predators would have more light to hunt them.

Panoche Hills. Photo by Scott Hein.

It was cool, beautiful, moonlit. Creeping along, a mile or two up the road, in our headlights we saw our first kangaroo rat. We crept along, it hopped along on its big kangaroo-like legs, staying on the road. Not far ahead we saw an owl on a fence post, proving our point about predators.

A few miles ahead, another kangaroo rat, then another. None in the pass. I was glad there were no cars. In our 12-hour drive, we saw fewer than 10 vehicles. As midnight approached, we turned around at Mercey Hot Springs, and headed west.

For me, in one day with a good guide, Panoche went from being a large, arid grassland valley to becoming a place. A rich tapestry of landscape, watersheds, wildlife, history, relationships, what we’ll see in different seasons. A place of many parts.

Panoche, Little Panoche, Vallecitos. Panoche Hills, Tumey Hills, Ciervo Hills. Griswold Canyon. Silver Creek Ranch. Diablo Range rugged blue oak slopes. Grassland. San Joaquin Desert. Sinuous creeks. Cottonwood oases. New Idria.

Panoche Valley at sunset. Photo by Al Johnson.

Maybe we might have seen a San Joaquin kit fox if we’d driven another few hours. We know they’re there. Sunset and sunrise are probably the best times. Maybe they were hiding from the owls.

A sighting is more likely during the breeding season when the pups are active. Regardless, we saw much more than could be expected in one trip.

We’ll return many times. We’ll lead tours. In the future, Save Mount Diablo might help with some conservation effort or some legislation. As with John Muir, by writing articles, by informing more people and more decision makers, more conservation will result.

In July, we were back at it, checking out the two other best locations for San Joaquin kit fox, getting to know more of the San Joaquin Desert, exploring more of the Diablo Range.

Top photo by Al Johnson.

Seth Adams is Save Mount Diablo’s Land Conservation Director. He focuses on  advanced policy, land use, and advocacy; government relations; acquisition projects; and educational and media programs. Among his accomplishments are participation in preservation of tens of thousands of acres; creation of Urban Limit Lines; aid in development of hundreds of millions of dollars of conservation funding; the East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservation Plan and the Concord Naval Weapons Station Reuse Plan; new recreational trails such as the 30-mile Diablo Trail; and reintroduction of endangered peregrine falcons to Mt. Diablo. He has been involved in many political campaigns throughout Contra Costa County and the East Bay.

advanced policy, land use, and advocacy; government relations; acquisition projects; and educational and media programs. Among his accomplishments are participation in preservation of tens of thousands of acres; creation of Urban Limit Lines; aid in development of hundreds of millions of dollars of conservation funding; the East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservation Plan and the Concord Naval Weapons Station Reuse Plan; new recreational trails such as the 30-mile Diablo Trail; and reintroduction of endangered peregrine falcons to Mt. Diablo. He has been involved in many political campaigns throughout Contra Costa County and the East Bay.