Story and photos by Bruce and Joan Hamilton

How Did Wildlife Fare in the SCU Fires?

As we pull into the parking lot at Sunol Regional Wilderness one June morning, it’s already warm. A T-shirt-and-shorts day. But right after introductions, wildlife biologist Amanda Murphy hands us each a pair of heavy knee-to-toe Kevlar gaiters. Protection from rattlesnakes, she says.

Murphy’s an expert in a species much rarer than rattlers: the Alameda whipsnake. It’s an agile creature that can rise up like a cobra, grab a branch with its prehensile tail, and glide (or is it fly?) across trees and shrubs. It’s also a threatened species that only lives in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

A glimpse would be more than welcome. But mostly we want to learn how whipsnakes and other small vertebrates have fared in last fall’s Santa Clara Unit (SCU) Lightning Complex fires.

With our calves encased in Kevlar, we hop in Murphy’s truck. One thing we notice right away: This researcher drives slowly. Dirt roads can be bone-jarring, and we wonder aloud if it’s for our benefit. But no, she says, it’s for the snakes.

In our first 10 minutes, her caution enables us to see an olive-green ripple crossing the road. “Coluber constrictor,” she announces. Looking at my blank expression, she kindly adds: “yellow-bellied racer.”

Murphy preparing to check traps

A contractor for the East Bay Regional Park District, Murphy trapped small animals in the Ohlone Regional Wilderness for three years before the fire. Now she’s halfway through her fourth year, eager to compare pre- and post-fire results. Each day of the study, she drives from Sunol Regional Wilderness into the Ohlone, a round-trip of about 30 miles.

She repeats that journey 45 times in spring and early summer, often by herself, to catalog, measure, mark, and set free whatever she has caught in 88 far-flung traps. Yet she approaches our first trap as if it’s her first. “Just like Christmas!” she says. “I get a warm and fuzzy feeling from snakes and lizards.”

Murphy grew up in the East Bay’s Castro Valley, riding horses and catching snakes and lizards in the hills. As a college student, she joined teams re-establishing peregrine falcons in Montana and California (near Mount Diablo and in the Sierra).

She later moved to Central and South America, where she studied monkeys while living with indigenous tribes. After giving birth to her first son, she returned to California to become a local snake and amphibian expert. “When I was about three years old, I said I was going to work with monkeys and snakes,” she said. “And I did.”

Fifteen years ago, she started the company she runs today, Wildlife Science Consulting. At times, the work is a family affair. Both she and her husband, Caleb, also a wildlife biologist, have federal and state permits to trap and handle wildlife. Her sons, Geno, 21, and Liam, 16, help them build traps.

The devices, loosely based on a design from the 1950s, consist of long, wavy fiberboard walls about 18 inches high with wire “minnow trap” cages attached at both ends and sometimes in the middle. Creatures coming up or down a slope hit the wall, follow its sinuous path, and, if Murphy is lucky, walk into a funnel leading to a hole in the wire cage.

Inside the cage, a piece of clear plastic plops down over the hole so captives can’t escape. A small square of plywood over each cage provides shade while they wait (no more than 24 hours) to be marked, measured, and counted.

Murphy looking into a trap with two gopher snakes

In addition to the Kevlar gaiters, Murphy wears gloves (to protect herself from bites and bacteria), and has a long metal snake stick to keep rattlers at a distance. She captures rattlesnakes about twice a week, and whipsnakes about once a week.

Murphy knocks on the plywood covering of our first trap. There being no rattling sounds, she bends over and peers into the cage.

We have a yellow-bellied racer (Coluber constrictor mormon), just like the one on the road. She holds it up and marks it with non-toxic ink. These racers are common, but also proof to her visitors that the wilderness’s parched hills are full of life.

Yellow-bellied racer

That message is reinforced by other finds, including alligator lizards (Elgaria multicarinata); Coast Range fence lizards (Sceloporus occidentals bocourtii), with one female full of eggs; and a deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), our only truly warm and fuzzy creature of the day.

The bug-eyed mouse is cute, but not strategic. Upon release, it runs right back into another trap. Murphy sighs and sets it free in a more distant spot.

Gopher snakes (Pituophis catenifer) command attention because 1) they are huge and 2) they look so much like rattlesnakes (but have no rattles). The first one we find is wiggly, thick, and more than three feet long.

Holding it behind the head, Murphy has to raise her arm high to keep it off the ground. We wonder how it could have possibly slithered through the 1.5-inch hole in her trap.

Murphy explains that snakes can not only expand to eat large prey, they can contract to fit into small holes. Later, we find a pair of gopher snakes entangled together in the same cage, a startling, slightly creepy sight to the uninitiated.

Our most graceful find of the day is a juvenile California kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae). It’s small now, but someday should be able to take on a gopher snake or even a rattler. When Murphy places its loopy black-and-white body on a downed tree limb, it hangs around for pictures. As an apex predator, perhaps it can afford to be nonchalant.

Juvenile kingsnake

“You’re good luck!” Murphy says kindly. But we still haven’t seen a whipsnake. They use a variety of habitats, including grassland, streamside, and oak woodland. But they seem to require at least some coastal sage scrub, including plants such as sagebrush and bush monkeyflower.

Coyote bush is not so hospitable to whipsnakes, perhaps because it can grow to be tall and dense, blocking the sun they need to keep their body temperature at 93 degrees (which is lethal for some snakes). Similarly, fire suppression threatens whipsnakes by producing more shady areas.

Murphy says that cliffs often have good basking areas for whipsnakes, as well as Coast Range fence lizards, their favorite prey. So there’s hope in the air as we walk steeply downhill to one of our last trap lines for the day.

Whipsnakes evolved from ancestors in Baja California. Over time they expanded their range north into California. Here in the northern part of the Diablo Range and in hills closer to the coast, an inland sea isolated one whipsnake population for 1 to 2 million years.

That population is now called the Alameda whipsnake. Over the millennia, it developed a different coloration, including bolder stripes. It was “kind of an island effect,” Murphy says.

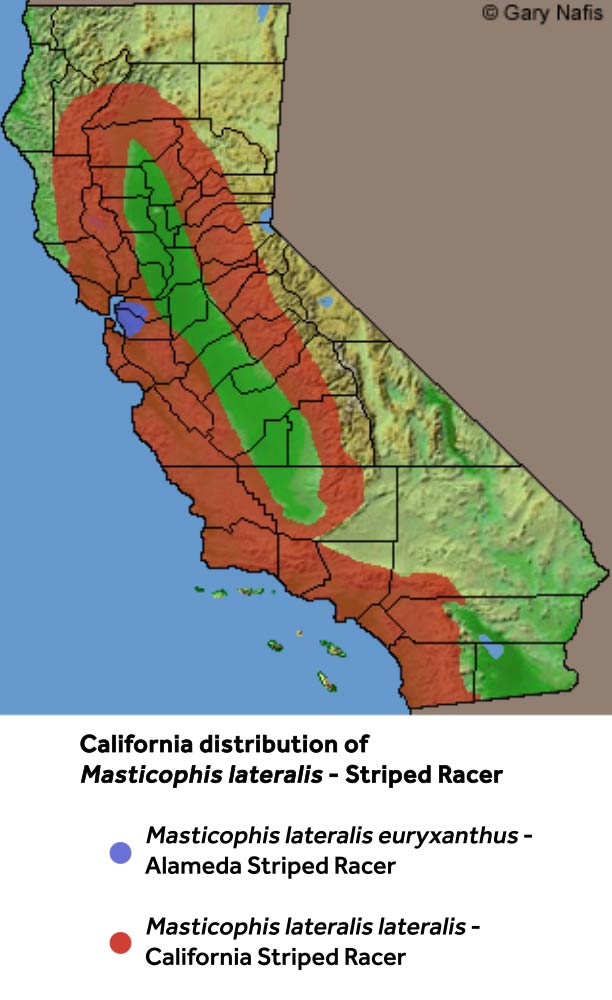

Today the Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) is listed as a “threatened” by both the state and the federal government, while its cousin, the “chaparral” whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis lateralis), is common in the Sierra foothills and along the southern and central California coasts.

Map by Gary Nafis

Aided by Murphy’s data, the East Bay Regional Park District is working to protect key habitat for the Alameda whipsnake, including 438 acres here in the Ohlone Wilderness. Save Mount Diablo’s been working to protect the Alameda whipsnake, too, through negotiations with developers in the northern part of the Diablo Range.

“If you use the regulatory power of the Endangered Species Act to protect rare species, all of the other species benefit, too,” says the organization’s Land Conservation Director Seth Adams.

Murphy checking a trap

When we arrive at Murphy’s cliffside traps, we’re pleased to see a sunny, rocky area dotted with sprays of gray-green sagebrush that seems perfect for our quarry. Murphy knocks on the first trap. There’s a rustling inside. She bends over double, lifts the plywood, picks up the wire cage, and triumphantly pulls out . . . a lizard.

The lizard is golden, like a mini-Komodo dragon, with long, delicate toes that would be the envy of any big wall climber. It’s a California whiptail (Aspidoscelis tigris munda). Not what we were expecting. But Murphy is delighted. She’s only caught California whiptails at lower elevations in the Ohlone before, and this is the first one she’s seen since the fire. It’s a survivor.

A whiptail lizard

As we rumble down the road back to Sunol, we stop to look at a killdeer poking around the muddy edge of a stock pond. Murphy calls this “Rattlesnake Pond,” based on many sightings.

Kevlar gaiters are a must here, she says. Her husband was bit by a rattler once, and after yelping and flailing his leg to dislodge the attacker’s fangs, he walked away without a scratch. But only because, at her insistence, he had his gaiters on.

As we step closer to the desolate-looking pond, Murphy points out an abundance of non-threatening life: chorus frogs, pond turtles, red-legged frogs, Diablo Range garter snakes, damselflies, and dragonflies.

The garter snake (Thamnophis atratus zaxanthus) makes me do a double take: at first it appears to have the same yellow stripes we’ve seen on whipsnake pictures. But the garter snake has a stripe down the middle of its back as well as stripes down the sides. Murphy explains that a whipsnake would never have that “dorsal” stripe.

Two Diablo Range garter snakes

We end our drive feeling reassured by the many scaled, winged, and furry creatures that have survived the burn. It’s too early to draw conclusions about the SCU fires’ precise effects on wildlife, but Murphy says that they were fires of moderate heat and medium speed, “which is likely very good.”

Most animals had time to run away, and those that live in rodent holes, such as snakes, lizards, and small mammals, probably had excellent protection. Most notably, she’s capturing just as many Alameda whipsnakes this year as she did in the years before the fire. Even smaller snakes, like the first-year juvenile kingsnake and yellow-bellied racer, have managed to survive.

But Murphy’s work may eventually reveal losses, too. Past research has shown animals that use burrows (snakes, lizards, small mammals) tend to thrive after fires, while amphibians, which prefer shade and leaf litter, do better in places where fires are less frequent.

Of course we didn’t see an Alameda whipsnake on our outing. But Murphy caught one yesterday and will try again tomorrow. Mostly she’s happy to be roaming the East Bay hills and contributing to the East Bay Regional Park District’s efforts to protect wildlife.

“I never get tired of this work,” Murphy says. “You never know what you’re going to find.”