Mountains have an extraordinary power to move us deeply in a multitude of ways. A glimpse of blue ranges fading mysteriously into the luminous distance can revive memories of long-forgotten places of childhood fantasy.

A touch of gold on a peak poised high above the clouds can evoke visions of a higher, more perfect realm of existence close to heaven.

Vistas of mountains soaring gracefully over the surrounding landscape can inspire masterpieces of art and photography, revealing fresh new views of the world around us.

In the thunder, lightning, wind, and clouds that envelop them, mountains also reveal powerful forces beyond our control, physical manifestations of a greater reality that can overwhelm us with feelings of wonder and awe.

The immense circle of the horizon viewed from the summit of an isolated peak like Mount Diablo can open us to an exhilarating experience of the vastness encompassing the limited world of daily life.

Because of their evocative nature, mountains have come to reflect the highest and deepest values and aspirations of cultures throughout the world.

The Monastery of St. Catherine at the foot of Jebel Musa (Mount Sinai), Egypt. Photo by Edwin Bernbaum

The Bible singles out Mount Sinai as the awe-inspiring place of revelation where Moses received the Ten Commandments, the basis of law and ethics in Western civilization.

Looming in isolated splendor over the vast plateau of Tibet, the magnificent white dome of Mount Kailas inspires millions of Hindus and Buddhists with the aspiration to attain the heights of spiritual enlightenment.

The perfection of the sublimely shaped cone of Mount Fuji embodies the quest for beauty and simplicity that lies at the heart of Japanese culture.

For many in modern society, non-climbers as well as climbers, the summit of Mount Everest symbolizes their highest goals, whether spiritual or material.

Visible from miles away, Mount Diablo looms large not only in the landscape, but in the spiritual beliefs and stories of the Indigenous peoples of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Delta, and parts of the Central Valley.

For some of these tribes, the mountain was the place where the world was created, and the power of that creation still resides there.

Even today, Mount Diablo is an important, powerful, and sacred presence. It is looked upon with respect and treated with reverence by the Native people of the region.

From the Coast Ranges of California to the Himalaya, people around the world look up to mountains as sources of meaning, renewal, wisdom, creativity, and vision.

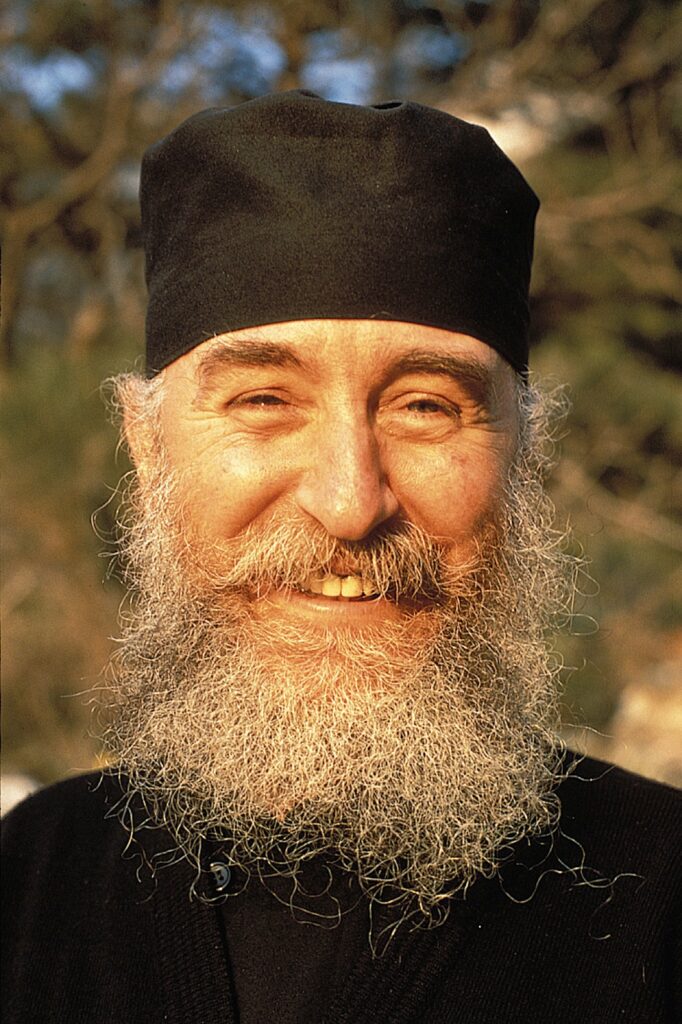

Monk on Mount Athos, Greece. Photo by Edwin Bernbaum

Throughout history sages, yogis, hermits, and prophets have gone to mountains in search of wisdom and transformation.

The Chinese have long regarded the heights of misty peaks, far from the distractions of profane daily life, as such ideal places for pursuing the higher, spiritual aims of religion that the Chinese expression for embarking on a religious path means literally “to enter the mountains.”

The plains Indians of North America, such as the Lakota and the Cheyenne, seek out high places as places of power for engaging in vision quests that will determine the course of their lives.

Orthodox Christian monks and hermits seek communion with God on Mount Athos in Greece and Mount Sinai in the Middle East, as Saint Symeon has so evocatively written:

“He [the monk or hermit on Athos] becomes one who is pure and free of the world and converses continually with God alone; He sees Him and is seen, loves Him and is loved, and becomes light, brilliant beyond words.”

Speaking of Mount Kailas—the most sacred mountain in the world for more than a billion people, followers of at least four different religious traditions—Tibet’s most famous yogi, Milarepa, had this to say:

“This is the great place of accomplished yogis;

Here one attains transcendent accomplishments.

There is no place more wonderful than this,

There is no place more marvelous than here.”

Mount Kailas, Tibet. Photo by Edwin Bernbaum

Around the fourth century, Chinese literati started going up to mountains to escape the stultifying strictures of the imperial court and recapture a sense of spontaneity by walking, climbing, and composing poetry and art.

In the eighth century, expressing an intimate connection with nature, Li Bo, one of China’s greatest poets, wrote:

“Up high all the birds have flown away,

A single cloud drifts off across the sky.

We settle down together, never tiring of each other,

Only the two of us, the mountain and I.”

Mountain climbing for sport and recreation, rather than strictly religious purposes, actually began in China more than a thousand years before the birth of alpinism in Europe in the late 18th century.

Since then, numerous European poets and writers such as Percy Bysse Shelley and Thomas Mann have composed works based on the power of mountains to move the human spirit and evoke a sense of the sublime.

The philosopher and poet Wolfgang Goethe wrote of his first view of Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps:

“We gave up at once all pretensions to the infinite, for even the finite that appeared before us eluded the grasp of our thought and sight.”

The beauty of various features of mountains makes them natural sources of inspiration for works of art and photography, as well as literature.

In the hands of a master, a painting of a mountain landscape does more than portray a beautiful scene: it evokes visions of a reality more intense and meaningful than the one of our usual experience.

We see everything, not only mountains, in a new and brighter light, one that connects us to nature and reveals aspects of the world and ourselves that we have overlooked or ignored.

In a passage that resonates across cultures, the great Chinese landscape painter, Guo Xi, wrote:

“The din of the dusty world and the confines of human habitations are what human nature habitually abhors: while, on the contrary, haze, mist, and the haunting spirits of the mountains are what human nature seeks, and yet can rarely find . . .”

Ansel Adams added these thoughts on the intended effect of his photographs of the Sierra Nevada:

“We all move on the fringes of eternity and are sometimes granted vistas through the fabric of illusion.”

Views of mountains as places of inspiration and renewal helped give rise to the environmental movement and have continued to play a key role in galvanizing support for parks and protected areas, including land trusts such as Save Mount Diablo.

Mount Diablo. Photo by Stephen Joseph

John Muir, who played a leading role in protecting Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada in the 19th century, and David Brower, whose efforts kept the US Congress from damming the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon in the 20th century, drew heavily from deeply felt personal experiences wandering among and climbing mountains.

They saw these experiences as prime examples of pristine nature essential for our physical and spiritual well-being.

Muir wrote of the benefits that come from mountains as a major reason for protecting the environment in general:

“Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

Henry David Thoreau, whose writings continue to inspire the modern environmental movement, wrote of the positive, transformative influence of mountains:

“There is something in the mountain air that feeds the spirit and inspires. Our thoughts will be clearer, fresher, and more ethereal, as our sky . . . our understanding more comprehensive and broader, like our plains . . . our intellect generally on a grander scale, like our thunder and lightning, our rivers and mountains and forests.”

In coming to special mountains like Mount Diablo, many seek to transcend the superfical distractions that clutter their lives and to experience something of deeper value.

Such places serve as windows through which we can catch glimpses of a more meaningful reality that makes life worth living and the environment worth protecting.

About the author

Ed is the author of the award-winning book, Sacred Mountains of the World. He will be teaching an online Zoom course on “Sacred Mountains of the World: The Heights of Inspiration” for Stanford Continuing Studies this spring, starting on April 18. The course is open to anyone interested in the subject. Information and registration can be found on the Stanford Continuing Studies website.