As part of our 50th anniversary celebration, we’ve been working with UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library to create a series of oral histories of the empowering individuals who helped create Save Mount Diablo. You can view the whole list and an overview of the project here.

Egon Pedersen grew up in Denmark during the German occupation in the 1940s. “It was a very, very hard time. You know, a lot of times the Germans would put a quarantine on, and we couldn’t get out all day and night.

“And it got even worse sometimes. They cut off the water, they cut off the electricity, so it was really tough, tough times.”

Though years of his childhood were lived in the shadow of the occupation, he was still able to enjoy the outdoors and develop a lifelong love of nature. He studied engineering in college and met his wife before moving over the ocean with her to California.

Move to California and Relationship with Mount Diablo

“My wife wanted to go to California because she had read about Yosemite. That was a big thing in her—and she said, ‘I want to go and visit the family and Yosemite. That’s the first place I want to go.’ Because she had seen and heard all about Yosemite.”

Egon and his wife Inger were constantly traveling, and went to Yosemite many times. But it was Mount Diablo, close to home, that would capture Egon’s heart.

Mount Diablo from Marsh Creek State Historic Park. Photo: Scott Hein

He became deeply familiar with Mount Diablo over numerous trips. “We could see this beautiful mountain out in the distance. It was one of the very, very first places we went to. . . . we liked going on picnics on Mount Diablo and hiking all the trails there.”

Eventually, Egon moved his family to Diablo so that they could have horses—living with Mount Diablo right outside his bedroom window.

“It was beautiful, because it was completely open country, and everybody had two or three or four or more horses. . . . You could just ride your horses in between everything.”

Once he began observing the rapid development of the 1970s that threatened Mount Diablo, it was hard to look away. “Every time we went on a picnic, there was a house there and a new house there.”

“We said, ‘We want to help these people [Save Mount Diablo].’ Because like I said, we had gone through so much to be so fortunate to live so close to the mountain, and we just loved the area. And so I said, ‘I’ll do anything I possibly can to help these people.’ So I went to their meeting.”

Leadership at Save Mount Diablo

“After a while, Mary Bowerman told me. . . . ‘Egon, we need a Vice President.’ And I said, ‘Well, I just want to help. I don’t think I’m—because I’m kind of a shy guy, and I don’t think I can live up to Vice President.’ She said, ‘Oh no, but that’s what we need, so if you want to help, this is it.’”

As Vice President, Egon built a relationship with California State Parks as a representative of Save Mount Diablo. “Every time there was talk about land acquisitions or donations to Mount Diablo, we always had to go and present it to the Board of Supervisors.”

Egon Pedersen (right) and California State Parks Peace Officer Scott Poole celebrating the 40th anniversary of Mount Diablo’s historical plaque in 2018. Photo by Cheri Easterly

Egon didn’t stop at being Vice President. In 1974 he stepped up to become President of Save Mount Diablo and served until 1977. He says that his duties didn’t change much, but the work continued as he advocated on behalf of Mount Diablo.

“I was writing a lot of things to the papers, to all the papers. Every time I wanted to comment on a bond issue or whatever there was coming up, I was writing letters to whoever I could.”

He wrote letters advocating for the protection of Mount Diablo to everyone, including the former Governor of California, Ronald Reagan, and it paid off.

“I just wrote him [Ronald Reagan] that Mount Diablo was a very important recreational area, and I said if he could consider some land, buying some land around [the mountain], that I really, really, really would appreciate it.

“And lo and behold, a couple of months after, he actually allocated money for buying land around Mount Diablo.”

In 1976, Save Mount Diablo completed its first land acquisition under his leadership. “We were just trying to be a little, peaceful group saving—getting money from contributions, buy a piece of land.

“And we bought the first piece of land. . . . It was on a corner of Marsh Creek and Morgan Territory [the ‘Corner Piece’]. We bought it from our own money we had saved. We bought that piece of land. So it was quite something.”

Speaking on Behalf of Save Mount Diablo

Hikers enjoying Mitchell Canyon in Mount Diablo State Park. Photo by Laura Kindsvater

Though Egon always saw himself as a “shy guy,” he found that it was easy to publicly speak about Save Mount Diablo’s work.

“I’ve found out when you have something in your heart, you can stand up and you can speak to anybody about anything, and it’s no problem whatsoever.”

He says, “If it’s something you really believe in, it’s something you love—and what could be better than to expand a beautiful place like that, with such a beautiful nature and flowers, and history?”

Egon would go speak at libraries and historical societies about Save Mount Diablo. He became the chairman of historical collections at Save Mount Diablo and built an extensive collection of historical pictures that he still readily shares.

“I probably have the biggest collection of historical pictures, so anybody writing a book about history of the area or anything, they always come and borrow all of my pictures.”

“I gave a lot of slideshows, and I started thinking that’s the best way. I was very much into the history, and I belonged to all the historical societies. . . . And then after that, it got to be a lot of word of mouth.”

Old car at Mount Diablo State Park. Photo by Egon Pedersen

Mount Diablo’s Historical Plaque

In 1978, it was Egon Pederson who advocated with the San Ramon Historical Society to get Mount Diablo officially registered as a California historical landmark.

Helping honor Mount Diablo’s significant historical and cultural heritage, the plaque can be seen just outside the visitor center on Mount Diablo’s summit.

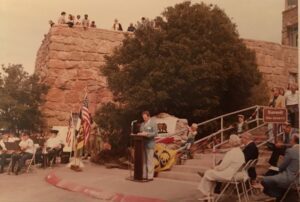

“I must admit that’s one of my big days in my life. The day I had there the band was playing, and I was unveiling the plaque.”

Egon Pedersen speaking at the Mount Diablo historical plaque unveiling ceremony in 1978. Photo by Chris Pedersen

How Save Mount Diablo Has Changed

Since its beginning in the 1970s, Save Mount Diablo has expanded and changed with the times while carrying on Mary Bowerman’s vision.

“What should I say, it’s become very, very professional. . . . I think it’s wonderful that they carry on Mary Bowerman’s goal to preserve the mountain and expand open space.

“And I really admire them expanding beyond Mount Diablo, also, because this is just as important. This is also open space for wildlife, so the more wildlife areas you can connect together, the more beautiful chance we have for survival of all the wildlife—plants and animals.”

“I don’t have any doubt they’re going to have a beautiful future. I don’t think I have to hope for that. I’m so confident.”

To read more about Egon’s life and work, view his full oral history.

To learn more about our 50th anniversary oral history project, read our Voices of Save Mount Diablo blog post.

Top photo: Egon Pedersen (center) and Mary Bowerman (right) unveiling historic plaque. Photo by Chris Pedersen